Overview

Common Law, the law applicable to all people in England and still applicable today,1 was created in the reign of Henry II (1154-1189). He introduced a new judicial procedure that was to shape the future of English Society and made possible the rapid growth of the English Common Law, in place of the various provincial customs still administered in the Shire and Hundred Courts. The Court of Chancery dealt with cases for which there was no provision under Common Law. Ecclesiastical courts exercised jurisdiction over matters which were dealt with by ecclesiastical law rather than by common law; such as immorality, defamation of character and breaking the Sabbath. Edward I (1272-1307) introduced Statute Law and the process of removing the judiciary from ecclesiastical or warrior backgrounds to those who studied at University and the five Inns of Court.

Late medieval England was known throughout Europe for its high rate of crime: a Venetian diplomat was compelled to observe in 1497 that " . . . there is no country in the world where there are so many thieves and robbers as in England; insomuch, that few venture to go alone in the country, excepting in the middle of the day, and fewer still in the towns at night, and least of all in London." Conflict between the noble families, corrupt local officials and lack of a reliable police force contributed to its unenviable reputation.

The gravest danger to public order was the organized criminal gangs of the late middle ages. There was a very practical reason for these men to band together: the commoner types of crime such as seizure of land, abduction, extortion, the theft of animals and game, highway robbery and carrying on of feuds required a number of miscreants to ensure success. Outlaws frequently made up their numbers. The Coterell gang terrorised Derbyshire and north Nottinghamshire during the 1330s and even monastic houses were involved in gang activity: in 1317 monks from Rufford Abbey were reported to have gathered around them a "multitude of men"and kidnapped Thomas de Holm as he passed by the abbey, robbed him of his goods, and held him for a ransom of £200.

Before the sixteenth century there was little semblance of an organised system of law enforcement. Studies have shown that Early Modern England (circa 1550-1750) had a large number of courts with a criminal jurisdiction and there was also numerous officers charged with enforcing the law and maintaining the peace. It has been described as a “much-governed country” and in comparison to other European states was distinguished by the overwhelming importance of royal, as opposed to seigniorial law, and the widespread dependence on unpaid amateur local officials. However, things began to change and the Tudors created the Star Chamber which protected the weak against the strong, and the ordinary law courts gained their independence and were no longer intimidated by local influences. Juries became less afraid of giving verdicts against the powerful.

It was during the reign of Charles I (1625-1649) that the next real changes to law and order can be observed. After 1632 he removed every constitutional check on his actions and ruled the land at his own will and pleasure and dispensed with Parliaments and dismissed judges who dared to interpret the laws impartially. These and other issues were important factors in the English Civil War (1641-1651).

As a result of the ‘Glorious Revolution’ (1688-9), the power of Parliament was increased and the foundations of our present society was laid, including the victory of law over arbitrary power. Justice and humanity which were now divorced from all party considerations, gained considerably – judges ceased to be removable at the whim of the Crown, trials were conducted with decency and a certain amount of fairness, cruel floggings and exorbitant fines ceased to be the weapon of party politics and a whole host of other benefits ensued.

Timeline

| 1739 | London magistrate opens office in Bow Street to deal with offenders |

| 1753 | Small group of constables; ‘Bow Street Runners’ set up to patrol the area. Other groups followed along the same lines |

| 1775 | John Howard publishes his ‘Report on the State of Prisons’ |

| 1780 | Gordon Riots |

| 1782 | Law and order became responsibility of the Home Secretary |

| 1789 | French Revolution |

| 1793-1802 | Wars with France |

| 1811 | Luddite Riots |

| 1823 | Peel’s Prisons Act improves states of gaols |

| 1829 | Metropolitan Police Act sets up police force in London. Name ‘bobbies’ is derived from Home Secretary’s name, Robert Peel. |

| 1830 | Swing Riots |

| 1831 | Burning of Nottingham Castle |

| 1835 | Municipal Corporations Act gives local authorities control over police |

| 1836 | Nottingham City police force established |

| 1839 | Metropolitan and County Police Acts – sets up county police forces |

| 1856 | Rural Police Act makes police forces compulsory in all areas |

| 1877 | All prisons to be under control of a prison Commissioner |

| 1968 | Nottingham City and County Police Forces amalgamate to become Nottinghamshire Combined Constabulary |

| 1974 | Petty Sessions replaced by Magistrates Courts. Quarter sessions and Assizes replaced by Crown Court |

The long 18th century

It was during the long 18th century, when England saw a dramatic strengthening of the ‘Bloody Code’ of justice; a reaction by the peers and gentry who held power, to the perceived increase in crime, particularly against property. In London the volume of crime continued to rise after 1760. During this period the rapid urban growth saw humanity crammed together in appalling conditions which led to an increase in disease and crime. Frequent harvest failures and the long wars with France played their part in increasing the misery for many. Recent research has shown that although there was an increase in what has been called ‘social’ or ‘economic’ crime (those deemed by the perpetrators as legitimate and those committed against property), the number of violent crimes – murder, robbery and hold-ups – were on the wane. However, the relationship between crime and economic and social conditions was rarely simple and had more to do with the complexities of human motivation rather than criminal behaviour. The geography of crime is another complex area; although the town was always perceived to be the crime-ridden, socially divided den of iniquity, compared to the harmonious village, this is untrue and at certain times crime rose rapidly in the countryside, more so than in urban areas.

The elite’s fear of the growing criminal activity saw the number of capital or hanging offences rise from 50 to more than 200 with the threat of the gallows being used as a warning to those prepared to assault both property and authority. This was a criminal law based on ‘Terror’ and was one of the bloodiest criminal codes in Europe. Regional studies show a close relationship between crime and economic conditions. When the American colonies defeated George III’s armies in 1783 over 130,000 men were discharged, many crippled or severely injured and unable to work. This had a knock-on effect with many women now being put out of their ‘temporary’ jobs which they had filled while the men were away at war.

Nottingham Castle on fire, 10 October 1831.

In 1809 the cotton hosiery trade which supported over half the population of Nottingham entered a period of over 40 years depression. Wage cuts and steep rises in the price of food gave rise to the Luddite Riots in 1811. Political unrest culminated in the Reform Riots of 1831 and the burning of Nottingham Castle.

Crime and lawlessness increased in the early years of the nineteenth century so that by 1808 a public meeting was held to try and come up with a remedy; which called upon the Aldermen of the town to employ more watchmen!

Punishment

Offenders could be brought before three principal kinds of court; Petty sessions, Quarter Sessions and the Assizes. Petty sessions were the lowest court and dealt with trying lesser offences or to enquire into indictable offences (replaced by Magistrates courts in 1974). The Quarter Sessions were held four times a year and dealt with more serious crimes than those at Petty Sessions but not as serious as those to be tried by an Assize Judge. Nottingham had been entitled to hold Quarter Sessions since 1449 and held them in June, October, January and April. Retford held a Quarter Session at Christmas and mid-summer and Newark held one at Easter and Michaelmas. More serious crime, such as homicide, infanticide, rape, robbery and burglary and offences which were too serious to be tried at Quarter Sessions were tried before a circuit Judge at the Assizes which were usually held twice a year, in the principal court in each county, ie the County Hall except in emergencies such as the Luddite troubles, when a special Assize would be convened. Nottingham came under the Midland circuit, one of six circuits. The visit of the Assize Judge was amongst the social highlights of the year and was a spectacle of pomp. However Judges often had little understanding about the lives and situations of those on trial and very often the jury would return ‘Not Guilty’ verdicts, as they were more aware of the offender’s circumstances. Quarter Sessions and Assizes were replaced by Crown Courts in 1974.

Punishments often had no bearing on the seriousness of the offence. Many were brutal and far outweighed the crime. The purpose of punishment can be divided into 3 categories; retribution whereby the criminal repaid his debt to society; the deterrent whereby others would be swayed against committing a similar crime by the prospect of hanging or a long prison sentence and lastly the reformative idea whereby prisoners were transformed by a period of time in prison. Capital punishment, transportation and to a lesser degree, fines were the main forms used against the convicted criminal, although whipping and branding had also been used in previous centuries. There was little other in the way of secondary punishment available before the nineteenth century because prisons were designed not as a place of punishment but rather to house those awaiting trial and sentencing or debtors.

For the majority, capital punishment remained the only way to deal with those who murdered but it was not so clear cut against offences against property. However, the nature of the offence played an important part in the decision making process. Highway robbers and burglars were more likely to be hanged than petty thieves. Evidence of premeditation, age and a past criminal record also increased the possibility of a capital conviction. Equally juries were reluctant to return a guilty verdict if the death penalty was the likely outcome. There is a school of thought that by being magnanimous and not always sentencing the criminal to death that the ruling class could both terrorize and command the gratitude of criminals and the public alike.

Another aspect of the public hanging of convicts was that of crowd control. Popular executions could draw large unruly crowds, causing problems for the local authorities such as drunkenness, blasphemy, singing of obscene songs. On 8th August 1844 William Saville was executed outside the Shire Hall for the murder of his wife and children. In the ensuing throng in High Pavement thirteen people, mostly children, died and fifty others were injured. Two later public executions in 1860 and 1864 were better controlled by the police and authorities.

One punishment which continued throughout the period was that of branding cattle and horse thieves. After the prisoner had been sentenced his hand was forced into a frame and a red hot iron was applied to his thumb, marking him for life!

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the system of law was beginning to collapse under its own weight. Enlightenment thinking and new social ideas began to be voiced, bringing pressure for change. Attitudes towards punishment changed and in 1819 the Select Committee on Criminal Law marked an important departure from the previous century with several minor offences being removed from the capital punishment list. Further attempts were made to reform the English criminal law with little success. By the 1830’s some progress was visible in the reduction of capital offences, finally giving way to the call for the total abolition of capital punishment, although this was not achieved until 1965. However, during the intervening century other revisions were made, such as the abolition of gibbeting (1834) and public executions (1868).

The major secondary punishment of the eighteenth century was transportation to penal colonies. The 1718 Transportation Act allowed courts to send convicted prisoners as indentured labourers for terms ranging from 7-14 years. Originally used as a method of ridding the country of unwanted political undesirables, when many were sent off to the American colonies later this method was used to rid the country of many undesirables. On the loss of the American colonies the recently discovered continent of Australia was the ideal place to rid the country of delinquents. In the interim many convicts were kept on ‘Hulks’ in the Thames near Woolwich. Needless to say the conditions both on and around the ships were undesirable and a long-term policy was needed. Botany Bay in South East Australia was chosen as the first settling place for convicts and it suited the purpose because of its harsh and uninviting nature. Transportation reached its peak in the 1830s when over 7000 men and women from England and Ireland were transported. Transportation came to an end during the 1850s. By this time prison had taken over as the secondary means of punishment. However, during the late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century prisons had been transformed from merely a holding place into one of reform and rehabilitation of convicts. (see below for Prisons).

The advent of the Police Force

The history of the police in England and Wales goes back as far as the Saxon tythingmen. In the middle ages policing was governance through self-regulation, based on local community units of the tything where members had a responsibility for maintaining the law. If the law was being broken people were expected to make a ‘hue and cry’ – with other members of the community they would seek to capture the felons and take them to the hundred or borough court. Over time the tything man evolved into the parish constable, appointed to maintain the king’s peace and enforce the king’s law. His role involved taking those apprehended before a local court and receiving the fees and payments for doing so, as this remained an unpaid community function. All townspeople were eligible for the unpaid post of parish constable which was for the duration of one year. He continued his own work alongside that of parish constable and could be called upon to arrest and look after offenders until their conviction, often at their own expense. Needless to say many paid others to perform their duties which opened up the system to bribery. Nottingham had three constables; one for each parish. In times of unrest, such as the Luddite and Reform riots special constables were sworn in.

The nightwatchmen or ‘Charlies’ were the men who policed the towns by night and were privately financed by Watch Committees, usually formed by shopkeepers and property owners. In 1830 the Nottingham nightwatchmen were declared the most inefficient in England for a town of its size.

It is from the 1800s that this survey of the police in Nottinghamshire will begin. By the eighteenth century there were growing concerns over law and order in England. It is difficult to gauge exactly why this concern emerged at this time as very few statistics were kept indicating an increase in levels of crime and disorder, although statistics gathered after 1805 and studies of indictments and other court records show an increase in the levels of larceny into the middle of the nineteenth century, along with riots during periods of bad harvests and in wartime when military recruitment increased. Many of these fears were exaggerated by the lurid tales of crowd violence during the French Revolution. The government in 1830 found themselves up against the agrarian unrest of ‘Captain Swing’ and Reform Bill riots. In Nottingham this culminated in the burning of Nottingham Castle in 1831.

By the time Peel became Home Secretary in 1822 there was already an undercurrent for police reform and during the second quarter of the nineteenth century there was a flurry of legislation which saw the introduction of the Metropolitan Police Act 1829, leading to professional Police Forces being established. This was followed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835 which required the establishment of a watch committee to supervise a police force, in chartered boroughs. The 1839 Rural Constabulary Act permitted Police Forces to be set up in rural areas but left the decision to establish such a force in the hands of the county magistrates and finally the 1856 County and Borough Police Act made the formation of police forces obligatory for both county and boroughs.

The present day Nottinghamshire Constabulary is the product of four forces which were created between 1836 and 1840; all set up despite strong opposition at a time of social and economic turmoil but necessary to tackle the onset of growing crime and violence through a more organised system of policing. However, it was not all plain sailing, and many police forces, especially county forces were unpopular and ratepayers protested at the cost of the force.

In 1968 the Home Secretary proposed that there should be a reorganisation among police forces of many areas and the County and City Forces were brought under the one umbrella with Mr John Browne as the Chief Constable.

Nottingham City Police

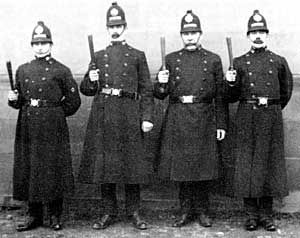

Nottingham policemen of the 1890s.

Nottingham City had previously had a police establishment of three permanent constables, 100 part time petty constables and a night watch of between 40 and 50 private watchmen plus a corporation watchman for the Shambles. An embryonic police force was established in 1836 but consisted of three entirely separate forces; Night Police, Day and Evening Police, all of which were completely uncoordinated even as late as 1841. A full time Police Chief was appointed in 1851, and later renamed Chief Constable in 1860.

The Watch Committee, which was initially in overall charge of the constables, took their duties very seriously sometimes to the detriment of 'good' policing and it was only with the onset of serious trouble at times of elections that progress was made in the satisfactory policing of the borough. By the mid-nineteenth century Nottingham had grown from a market town into a fully industrial town with many new problems; cyclical trade slumps, unemployment growing numbers of workers crammed into poor housing, poor sanitary conditions and a growing awareness of politics and radicalism.

By 1854 a Criminal Investigation Department had been established and by the end of the century the force consisted of 283 men serving a population of 240,000. Further departments including a river patrol, police dogs and women police officers were introduced during the early years of the twentieth century. Nottingham City Police was the first force in the country to introduce a two-way radio communication system in 1932 and together with the introduction of the mechanised wing in 1931 it was estimated that crime was reduced by 13.5% in the first year of the joint operation. The mechanised wing was formed to enable speedier and more efficient use of officers to arrive at scenes of crime and incidents. Motor vehicles were fitted with two-way radios connected to the central switch board and could be quickly despatched to an incident and able to report back on their findings. Nottingham was also the first force to set up a forensic science laboratory which remained in the city until its transfer to Cambridgeshire in the 1970s.

In 1958 tensions in the then slum district of St Ann’s erupted into race riots between white and black residents creating a major policing problem.

Nottingham City Police was famous for its very tall police officers; PCs Dennis ‘Tug’ Wilson (7' 2½ inches) and Geoffrey Baker (6' 8½ inches) who were approached and recruited into the force. Both men had been pall bearers and part of the cortege party at the funeral of King George VI in 1952. It also had a fine background of sporting activities including boxing, football, cricket and swimming.

Probably the most famous and influential officer of Nottingham was Captain Athelstan Popkess, OBE and CBE (1930-1959); who served as Chief Constable for 29 years before his career was abruptly cut short over an issue of the constitutional question of control of the police. A report into financial irregularities by some City Council members was demanded by the Watch Committee and refused by Popkess. He was suspended under the Municipal Corporations Act 1882 as unfit for office. Intervention by the then Home Secretary saw Popkess reinstated but he retired that same year. The "Popkess Affair" was a prime factor in the appointment of the Royal Commission and the subsequent Police Act 1964 which sought to establish the respective powers of the Home Secretary, a Police Authority and the Chief Constable.

Nottinghamshire County force

The 1835 Municipal Corporations Act applied to 178 boroughs in England and Wales and was to reform local government. One of the tasks of the new town council was the appointment of a Watch Committee, which was to appoint and supervise the town police force. The new police districts were to be formed in towns with a population in excess of 10,000. There was also the provision for forming such police in other districts where the government felt it necessary to do so.

Both Newark Borough (population of 10,000) and Retford Borough (population of 2,491) set up forces in accordance with the 1835 Act. Newark continued to have its own police force until 1947 when it amalgamated with the Nottinghamshire Constabulary. Retford managed with a day constable and two watchmen and later a Superintendent. There seems to have been little enthusiasm for paid policemen but by 1840 the old workhouse had been converted into a police station and temporary prison. The County Police Act 1840 provided for voluntary consolidation of small borough forces with larger county forces and in January 1841 Retford Borough Police consolidated with the County Constabulary.

The Southwell Quarter Sessions proposed on 21 November 1839 to inaugurate a Chief Constable, eight Superintendents and 33 constables for the County of Nottinghamshire and thus set up its first police force in 1840. As with other new institutions, such as the Poor Law, in this period the new County Constabulary met with a certain amount of opposition and none more so than from the ratepayer. Complaints about the costs were vociferous; between 1842 and 1845 petitions were sent to Magistrates at Southwell complaining of the expense incurred by the force. The Nottinghamshire Quarter Sessions reduced the force from 42 to 33 in January 1842, unfortunately with the later outbreaks of Chartist activity the force was once again increased to around 80, despite the flood of angry protests from ratepayers and the desire that the “Rural police may be discontinued”. Much of the opposition was focused on the quality of men recruited to the force. Many of the first recruits did not stay long within the force and there was a constant need to replace them but finding those men of good calibre was difficult. It was felt that it would be preferable to have as, parish constables, ‘men who had an interest at stake and property to protect’. A parish constable would be a ratepayer, fit and of good character between the ages of 25 and 55 years and would be supervised. These men were in complete contrast to the men of the county constabulary, many of whom had been agricultural labourers, from the armed forces or had worked on the railway companies. It was not unknown for the county constables to get into debt or drunk! It is no wonder that many police officers were treated with little respect by the public. Their duties were fairly routine; patrolling the highways and by-ways, petty larceny, sheep stealing, drunkenness, poaching and vagrancy. The efficiency of the force was not regarded as high and certainly could not be classed as professional.

The first headquarters for the force was believed to be at Mansfield but this later transferred to the Shirehall, Nottingham. The force grew steadily with the rise of the population and by 1856 the force had 82 officers rising to 200 by the end of the nineteenth century. Almost a century later in 1946, six women constables were appointed and the rank of Chief Inspector appeared for the first time. There were now 592 officers and pressure was on to find a new headquarters which was located and purchased by the Police Authority at Epperstone Manor.

Nottinghamshire Combined Constabulary

The new force had officers in both the county and city carrying on their normal duties. It became evident that with the enlargement of the force and the introduction of the Criminal Justice Act in 1967, the growing demands on the police service and changes within society meant the new force had to adapt and quickly. There was a mounting need for more accommodation and in 1972 Sherwood Lodge, Arnold became the force’s HQ, although it was not fully occupied until 1979. The force became known as the Nottinghamshire Constabulary and included the old City and County forces.

One major challenge to the force was the 1984 miners’ strike. In the beginning they dealt with it alone but as the dispute grew worse, they had to call on the support of virtually every other force in England and Wales. At the time there were 25 collieries in the Nottinghamshire area and the ‘flying pickets’ brought serious divisions of feeling between local men and miners from other areas.

In 2009 the force has a manpower of: Police Officers 2448, Special constables 291 and PCSOs 241. For the first time they have employed a female Chief Constable in 2007.

Since the beginning of the amalgamated forces 2 police officers have been murdered whilst on duty.

The centenary of women joining the police force

During the First World War the lives of women were transformed with many previously male only occupations being undertaken by women, whilst the men were away at war. One such role was that of policing. These roles were voluntary and were there for the protection of women working in roles and areas where there was the possibility of problems from men, either servicemen or those working alongside them. The first woman to be sworn in as a police officer with full powers was in Grantham, Lincolnshire.

The inter-war period saw the increase in rights for women, including the vote and being allowed into careers in public office, previously barred to them. In 1920 the Baird Committee agreed that women could be appointed as police officers, but was up to the local authority to do this and they were to be restricted to work with women and children. The metropolitan Police Force was the largest employer of women officers. During this period some police forces involved the women officers more and more.

Once again during the Second World War women officers acted as escorts for evacuated children and those interned as ‘aliens’. Cornwall the last county to appoint its first policewomen but their status had grown thanks to the appointment of Barbara de Vitre, the first female member of HM’s Inspectorate of Constabulary in 1945.

Nottinghamshire’s first woman police officer was Eleanor Plumtre who was appointed in 1919, however her contract was terminated in February 1920 by The Watch Committee. A couple months later in April 1920, a job advertisement for two female police officers was put in The Nottingham Guardian. Cecelia Clark and Ethel Davies became Nottinghamshire’s next two police woman.

Their duties included observation work in connection with detection of crime, betting and licensing offences, taking statements from women and children in cases of indecency, enquiries connected to women and children, patrol duty on special occasions and escorting and finger printing females.

Over the next three decades the role and status of women police officers improved culminating in the Sex Discrimination Act, 1975, when Policewomen’s departments were dissolved and they became equal to their male counterparts, in both pay and conditions, although there were still hurdles to overcome in areas such as promotion. It was not until 1996 that the first female Chief Constable was put in charge of a UK police force.

In 1986, only eight per cent of Nottinghamshire’s officers were women. Today, the number of female officers is almost 600, which represents a significant improvement but is still not reflective of the 51 per cent female population of Nottinghamshire. Nottinghamshire has had two female Chief Constables; Julia Hodson in 2008 and Sue Fish in 2016.

Acknowledgements to the British Association for Women in Policing, '100 years of women in policing', Nottinghamshire Police and '100 years of service' for material for this section.

Gaols and prisons

Prior to the late eighteenth century there were few purpose built prisons so many of the gaols could be found in buildings such as rooms in Castles, Town Halls and other secure properties. In Nottingham during the reign of Henry VIII debtors and criminals were contained in prisons beneath County Hall on High Pavement and Nottingham Town Hall and Gaol on Weekday Cross. Until the late eighteenth century most prisons had been used to detain prisoners before they appeared in court, awaiting sentencing, or else an accommodation for debtors.

It was the philanthropist and reformer John Howard who made a first hand study of real conditions in prisons, including his visits to the Nottingham County Gaol in 1782 and 1788. He had begun work in this area with his 1777 publication, ‘The State of Prisons in England and Wales’, which highlighted the filth, squalor and prominence of ‘gaol fever’, a particular virulent form of typhoid which he claimed killed more prisoners than were hanged. Nottingham Borough Gaol was built on the side of a hill, with the different classes of prisoners accommodated on descending floor levels, the more serious the crime the deeper the cell. It took time for any improvements to occur and desire for prison reform waxed and waned throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It was in 1797 when the Grand Jury at the March Assize complained of the state of the gaol that work commenced on building 5 new cells and a day room. Countrywide there was a renewed enthusiasm for prison reform, especially in the post-Napoleonic war period after 1815. Nevertheless, as late as 1889 Mr Justice Willis visiting the cells exclaimed, “Good God! To think that men should have to live in a place like this!”

Before the 19th century central government had no responsibility for prisons, which were administered locally. However, some prisons were built by central government to house convicted felons, e.g. Leicester, Millbank and Pentonville. Women were held at Brixton and Fulham and juveniles at Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight. The Prisons Act 1877 transferred local gaols to the control of central government

County prisoners who were sentenced to anything other than hanging or transportation were sent to the House of Correction at Southwell which was opened in 1742.

The House of Correction on St John's Street, Nottingham was demolished in 1891.

The Nottingham House of Correction was built near Bath Street, Sneinton, on St John’s Street and was originally a two-roomed building in 1615. An extension was completed in 1806 but it took another 30 years before new premises were completed and a further 10 years before it complied with the Prison Reform Act and it became the town’s common gaol. Prior to that as with the Borough Gaol conditions within the House were primitive to say the least. As well as the poor accommodation and meagre food the prisoner was subject to tiring and monotonous tasks, specially designed to break the spirit. The treadwheel was erected in October 1825 – the machine was worked to provide power for a pump to lift water. The prison became so overcrowded that when the Home Office took over the running of prisons in 1879 it should have been closed but was deferred until 1882 when it was decided to build a new prison at Bagthorpe. Nottingham Gaol and the House of Correction were demolished in 1891.

In 1860 a thirty acre site belonging to the Duke of Newcastle on Hucknall Road was purchased by the War Office for Barracks. The present day Nottingham Prison on Perry Road, Sherwood was built between 1889 and 1891 and began taking prisoners from the House of Correction and the County Gaol shortly afterwards. It provided secure accommodation for 201 male prisoners and 31 female who were housed in temporary accommodation until 1894 when a specific block was built to house them. It was reconstructed in 1912 and today it has a maximum capacity for 550 male Category B prisoners, convicted of violent crimes and still classed as a danger to the public.

Shire Hall, Nottingham

Shire Hall, Nottingham.

The Shire Hall on High Pavement was rebuilt in 1770, and is sometimes referred to as the County Gaol (an unfortunate slip of the mason’s hammer named it the County Goal!) and was used to house debtors or those awaiting trial. It had also been a place of execution both inside and on the front steps. When the Victorians overhauled the prison system, the gaol was closed due to its appalling conditions and it lay empty from 1878 until 1995. The Shire Hall however, continued to house Nottingham’s criminal and civil courts until 1985 when the new Crown Court was built by the canal. A Police Station had been added in 1847 which was updated in 1907 and closed in 1986.

When the Shire Hall closed it remained empty for almost a decade before the Lace Market Heritage Trust took it over and transformed it into the Galleries of Justice Museum which opened its doors in 1995. As well as a being an interactive museum of crime and punishment it houses the Wolfson Resource Centre which explores the history of law, crime and punishment. It is also home to the Nuremberg Collection and other famous trials and numerous other archive material relating to the Police, Probation Service and legal personalities.

1. Common Law refers to law and the corresponding legal system developed through decisions of court and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes.