|

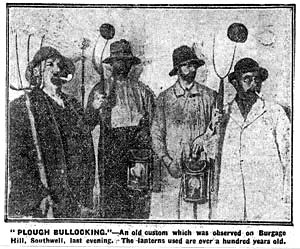

Plough Bullocking, Southwell, in 1926. |

Subject overview

Originally coined in 1846 by W.J.Thoms (the founder of Notes & Queries), the term ‘folklore’ has come to encompass seasonal customs, beliefs, legends, traditional arts, and similar activities. During the 20th century, the word acquired unhelpful twee connotations. Consequently, academics nowadays sometimes prefer the term ‘vernacular culture’, which is analogous to ‘vernacular architecture’.

In the past, folklore has been regarded as something restricted to ‘the common people’ and founded in olden times, transmitted orally from generation to generation. Modern research has shown that these concepts are misplaced; people of all classes have their traditions and beliefs. For instance, the aristocratic owners of a stately pile will happily tell you about their resident ghost, and whether or not they believe in it themselves, it is their folklore. While many traditions do indeed have a long history, they are often not as ancient as we might expect. New traditions continue to emerge, as for instance with the impromptu shrines of flowers and cuddly toys that now appear at the sites of accidents. Also, although oral transmission is a key process in folklore, we now recognise that printed and modern media also play important roles.

Nottinghamshire’s folklore

Nottinghamshire lacks any of the folklore compendia that have been published for other counties by the Folklore Society, the publishers Batsford, and the prolific author Roy Palmer. Consequently, there is an apparent low level of awareness of Nottinghamshire’s folklore among the general public. The notable exception is Robin Hood, whose tales have achieved worldwide fame thanks to the popular media. The tales of the Wise Men of Gotham also make a respectable showing. However, both these sets of tales are not so much folklore of Nottinghamshire but folklore about Nottinghamshire. They are encountered all over the country and overseas, but are not necessarily any more prevalent in the county itself, except in the tourist industry. (Robin Hood and his merry men will be getting an NHG guide to themselves, so only selected information will be given here.)

Outside of Robin Hood and the Wise Men of Gotham, other Nottinghamshire folklore is less well known. Most East Midlanders are likely to have heard of Nottingham Goose Fair, and some may have heard of the Maypole at Wellow, and Blidworth’s Cradle Rocking Ceremony. Nottinghamshire’s folk drama is also well known among people with an interest in folklore. There is, however, much more, as we shall see as I outline the main categories of folklore.

Seasonal or calendar customs

Seasonal customs are traditional activities that take place at particular times of the year, often associated with religious festivals; hence they are sometimes called calendar customs. We are all familiar with Christmas, New Year, Valentine’s Day, May Day, Halloween, Bonfire Night and similar customs that occur on a particular date. There are also the moveable feasts such as Shrove Tuesday and Whitsun whose dates occur so many days or Sundays either side of Easter. All these are national if not international phenomena. They are nowadays largely homogeneous and to a greater or lesser extent commercialised. In the past there was more regional variation, and Nottinghamshire also had its own special variants - for instance the Ball Game that took place in the streets of Eakring at Easter. There were once many maypoles in Notts (a subject researched by Frank Earp), and we still have the famous maypole in use at Wellow.

Two particular Nottinghamshire customs that deserve singling out are Plough Monday and Plough Sunday. There are differing definitions of Plough Monday in use in the county, which leads to some confusion. The ‘official’ date (as defined in the Oxford English Dictionary) is the first Monday after Twelfth Night (5th Jan.), but for some people it is the first Monday after Epiphany (6th Jan.), or the second Monday in January. All three usually occur on the same date, but every few years one definition will be either a week before or a week after the others.

In south Notts., up to World War II, it was the custom for children to go collecting from house to house asking people to “Remember the Ploughboys”, for which purpose they were often allowed a half-day holiday from school. Up to the mid 19th century, farm workers hauled a plough round by hand, and if they did not get sufficient reward, they would run a furrow across the lawn or drive, or do some other sort of damage. Unsurprisingly, this was actively suppressed by the authorities. Later in the 19th century the ploughboys went round performing a short folk play instead – the so-called ‘Plough Plays’. These seem to have been more acceptable; they survived until just after World War II in Tollerton. The plays have since been revived, with several groups such as the Calverton Real Ale and Plough Play Preservation Society (CRAPPPS) performing every January.

Another change since the War has been the emergence of a new custom – Plough Sunday – which occurs the day before Plough Monday. This consists of a church service in honour of the farming community and includes the blessing of a plough. The longest-running and probably the most impressive of these ceremonies is the Plough Sunday service at Newark. The plough is carried in procession by white-coated Young Farmers’ Club members from the Town Hall to the church accompanied by the Mayor, town officials, and numerous county dignitaries dressed in their regalia, followed by a long train of farmers and guests. The service is led by one or more guest bishops, who deliver a suitably topical sermon. In recent years, the Young Farmers have also carried a milk churn to the church, apparently because the dairy farmers felt left out.

Rites of passage

Rites of passages are ceremonies or customs that mark the various stages of a person’s life, in particular the transitions from one life stage to another. We can also include any associated beliefs under this heading. There are several parallel cycles:

- The biological life-cycle - pregnancy, childbirth, death

- Religious events such as baptism and confirmation in the Christian tradition, and circumcision in other religions

- Marriage-related customs - betrothal, stag/hen nights, weddings, honeymoons, and even divorce.

- Social landmarks - leaving school, coming of age (which in some cases may involve a religious ceremony), graduation from university, and retirement

- Special birthdays and anniversaries

Nowadays, these customs are increasingly guided by commercial enterprises – card shops, lifestyle magazines, the media, the hotel industry, etc – and therefore tend to be homogenous nationwide. However, there is some local variation, and there was even more in the past. For instance in Nottingham, whenever a girl in the lace industry was about to get married, her colleagues would deck her out in all sorts of lace oddments for her hen night. This has now developed into a more general tendency to wear fancy dress for both hen nights and stag nights.

One of the few references to Nottinghamshire in the journal Folk-lore, concerns an example of ‘couvade’ – the practice of a man taking to his bed and feigning illness while his wife is giving birth, in order to relieve her labour pains. In this case, the man lived in Wellow about 1908, and his friends spoke of him as “breeding for her” (E.Dunnicliff, 1933).

Occupational customs and folklore

Occupational customs and folklore occur within the work environment. They may relate to key stages of a task or project, to the stages of someone’s career, or even personal celebrations within a work context.

Many trades mark key stages of their work with special customs or ceremonies. In the construction industry, there may be a foundation laying ceremony, often involving the customer or a VIP, and with large buildings there may be a ‘topping out’ ceremony when it has been built to its full height. In Nottinghamshire, some of the best documented occupational customs relate to agriculture, notably the end of the harvest. The following account is an instance:

"A CORRESPONDENT, who signs himself 'North Notts.,' writes in the Daily News that a recent article in that paper reminds him of a similar custom which 25 or 30 years ago prevailed in the county of Notts., and [in] which he has, as a boy, frequently taken an active part. He adds - The last load of corn brought home from the fields was the occasion for the boys of the village to have a ride and to shout 'Harvest Home' for the farmers. This load would generally consist of the rakings of the field, and therefore not very valuable. Previous to our mounting the load for our ride we were careful to arm ourselves with branches of trees, the purpose for which will presently appear. On our journey from the field to the farmer's yard, the usual hurrahs would be lustily given, and at intervals of a few minutes a well-known speech or ditty would be recited by the leading boys, two of which I can yet remember:

God bless these horses which trail us home, They've had many a wet and weary bone. We've rent our clothes, and torn our skin, All for to get this harvest in. So hip, hip, hip hurrah.

In another the name of the farmer would be brought in thus:-

Mr. Smith he is a good man, He lets us ride home on his harvest van. He gives us bread, and cheese, and ale, And we hope his heart will never fail. So hip, hip, hip hurrah.

Then, Sir, curious and barbarous as it may seem, as we drew near to houses, it was the custom to bring out water and throw it upon us as we passed along, and from which we defended ourselves with the branches of trees. If we arrived safely home without a dowsing of water, the occasion was shorn of half the fun for the boys, but that was not the worst calamity. It was supposed that farmer Smith's yield of corn would not be so good. After arrival home apples would be distributed to the boys for their labour in shouting 'Harvest Home.'"

(‘North Notts.’, 1887)

When apprenticeships were the norm, there was a rich seam of industry-specific customs which marked the transition from apprentice to journeyman. Thus, in the coopering trade, the apprentice would be rolled around in a barrel and covered in beer and/or various sticky substances. Other trades often also included a similar degree of discomfort. Nowadays these customs are less predominant, although playing practical jokes on greenhorns (e.g. sending them for a “long weight” – i.e. a long wait) and retirement collections and do’s continue.

Personal events such as birthdays, weddings, new babies, and promotions are also celebrated in the workplace. These usually involve a card from colleagues, and cakes or drinks brought by the celebrant.

Traditional arts

In a word association game, the word ‘folk’ would most likely be associated with ‘song’ or ‘dance’, just two of the traditional arts. To these can be added folk drama and folk tales, as well as crafts such as corn dolly making.

Folk dance

While Nottinghamshire will have had its own folk dances – social dances, or possibly even morris or sword dances – very little has been recorded. Just to confuse matters, the name ‘Morris Dancers’ was used in Nottinghamshire and neighbouring counties for groups that went round houses performing folk plays but who never danced a step.

|

Mortimers Morris, one of Nottinghamshire's revival morris groups (© D. Shuttleworth, ActionAbility Ltd). |

Today there are several well known morris and sword dance groups, most of which were formed in the 1960s and 1970s, and all of which perform dance traditions from elsewhere in the country. Nottingham’s Foresters Morris Men are probably the oldest of these revival groups. Others include the Dolphin Morris (named after a long-gone Nottingham pub), Sullivans’s Sword, the Lady Bay Revellers, and Mortimers Morris (a female group). Details of these and other groups can be obtained from the three national morris organisations – the Morris Ring (www.themorrisring.org), the Morris Federation (www.morrisfed.org.uk), and the Open Morris (www.open-morris.org – or from the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS – efdss.org).

The EFDSS is also a good place to go for details of Nottinghamshire’s few native social folk dances. Barn dances and ceilidhs continue to be popular in the county, albeit thanks also to the folk revival. They are popular as fund-raising events and for weddings, where the progressional dances help break the ice as people move to new partners during the dance. One popular social dance is called “Nottingham Swing”, although this actually comes from Northamptonshire. There are other dances with “Nottingham” in the title – for instance “Nottingham Castle” and “Nottingham Races”.

Martin Kiff's Webfeet website is a good starting point for finding information on current social folk dancing activities (www.webfeet.org). It includes county listings.

Folk song

Folk songs fare better than folk dances in terms of what has been collected from the county. There are no dedicated published collections, such as there are for some neighbouring counties, the songs instead mostly being scattered among various manuscript collections. One notable manuscript source is the song book of John Reddish of East Bridgford, dating from the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. There is one published collection of local Christmas carols from Beeston that continue to be performed (I.Russell, 1997).

The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library of the EFDSS is a good first port of call, and has an online database in which you can search for songs collected from, or about, Nottinghamshire (www.vwml.org). Another good general online folk music resource is Martin Nail's English folk and traditional music on the Internet (www.englishfolkinfo.org.uk/folkmus.html?LMCL=phBDQc). The Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library also has a few manuscript folk songs. Unfortunately, neither of these sources is likely to include collections of football songs and chants, which should certainly be regarded as traditional, and therefore a form of folk song.

The tales and songs of Robin Hood and of the Wise Men of Gotham have already been alluded to. While Nottingham is named in many of the ballads concerning the escapades of the mediaeval outlaw Robin Hood and his merry men, these songs nearly all came from elsewhere. And indeed, there is continuing controversy, fomented by various tourist authorities, as to whether Robin Hood belongs to Nottinghamshire at all, to which can be added the question of whether or not Robin Hood was a real historical person. This is not the place to go into the respective merits or otherwise of these arguments, although it should be said that many of the ballads were post-mediaeval compositions and are therefore more likely to be fiction than fact. It is hoped that Robin Hood will be covered in detail in his own NHG guide.

Folk tales

The tales of the Wise Men of Gotham are a collection of tales of apparently foolish behaviour. The nub of the tales is that the residents of Gotham wished to keep King John away from the village. Versions differ. Either was expected to be passing through the village, in which case his route would become a public highway, or he was proposing to build a hunting lodge there. Either way, this could have been a burden on the villagers. They therefore resolved to behave as if they were mad in order to put the king off. Among other things, they were discovered building a hedge or fence around a tree with a cuckoo in, in order to stop it flying away. The Cuckoo Bush pub in Gotham is named after this tale.

While Gotham is particularly renowned for its ‘Wise Men’, it should be said that many of the tales of this genre are also found associated with other localities both in this country and abroad.

There have been numerous versions published of the tales. A useful introductory source that is also available online is F. Earp (1996).

Folk drama

|

Underwood Guysers, 1994 – pensioners reviving the play they first performed as children (© Peter Millington). |

Folk drama is the native folk art for which Nottinghamshire enjoys a national reputation. Folk plays are distinct from other forms of traditional drama such as Punch and Judy puppet shows and pantomime, although they may share a common heritage. Nottinghamshire’s folk plays were performed on and around Plough Monday in most of the county by groups calling themselves Plough Bullocks or Ploughboys, and at Christmas along the western border with Derbyshire by Guysers or Bullguisers. The plays were short, about ten minutes long, and were performed in rhyme. They were not, however, performed in theatres or village halls, but taken round farms, private houses and pubs in a manner similar to carol singers. In some places, it was customary for the actors to burst into the house rather than knock first, sometimes encountering domestic scenes that necessitated a hasty retreat. Mostly they were welcome, and they reaped generous rewards of money and/or refreshment.

There were four types of folk play in the county, for two of which the key character was a quack doctor. In the first of these, the hero Saint George or Bullguy has a swordfight with an adversary, often called Slasher, whereupon the Doctor is brought in to cure the loser. The play ends with requests for money from Beelzebub and a variable number of extra characters each with their own rhyme. The whole affair usually ends with a song. This version is the most common type nationwide, but was mainly only performed in the western half of Nottinghamshire – at Christmas along the Derbyshire border, and on Plough Monday in a band extending from north of Mansfield south to Kimberley. These plays were still being performed traditionally by children in the Selston-Brinsley area at least as late as the 1970s, although the length of the script had been much reduced.

|

Tollerton Ploughboys, Notts Guardian 1950 (Courtesy of the Evening Post). |

The second type of quack doctor play is the so-called Recruiting Sergeant play. These are often called Plough Plays due to their association with Plough Monday. The plot is arguably more complex, with a scene in which the Recruiting Sergeant persuades the Farmer’s Man to desert his Lady Bright and Gay and enlist in the army. The Lady then takes up an offer of marriage from Tom Fool. Dame Jane enters with an illegitimate baby, which she tries to dump on Tom Fool. At this points Beelzebub, Eezum Squeezum or some other character comes in and knocks Dame Jane down – a case of assault and battery rather than a fight – and the Doctor is called in to perform comical diagnoses and cures. While there is an essence of plot here, an alternative view is that these plays are little more than a parade of characters or a sequence of vignettes. If so, this does not detract from their entertainment value. Plough Plays are found in the eastern half of Nottinghamshire, and the evidence suggests that they may have spread there from Lincolnshire during the 19th century. The last known traditional group was the one from Tollerton, who continued performing into the 1950s. Plough plays were revived in the 1970s, and there are now several groups performing, for instance the Calverton Real Ale and Plough Play Preservation Society.

The remaining two types of play occurred in the north of the county, overflowing from Yorkshire. The Derby Tup is a dramatised song – a variant of the Derby Ram - which describes the attributes of a giant tup or ram, played by someone with a sheep’s head on a stick (usually not a real one), bent over and covered in a sheepskin or blanket. In a short dialogue intervention, a butcher is called to “stick the tup”, which he eventually does, and a little boy with a bowl is there to “catch the blood”. The song then resumes with verses concerning how the various body parts were used, for instance, using the ears to make leather aprons, the eyes as footballs, and so forth.

The Old Horse or Owd ‘Oss was also a dramatised song, this time with no dialogue. The song describes an old worn-out horse. The horse was portrayed in a similar fashion to the Derby Tup, this time with a horse’s skull on a stick, painted and with the jaws rigged to snap shut at the pull of a string. During the song, a blacksmith tried to shoe the horse with predictable horseplay.

Details of Nottinghamshire's folk play performers can be found in the Master Mummers Directory of Folk Play Groups (www.mastermummers.org/groupslist.php).

Child-Lore

Child-lore is the folklore belonging to children rather than folklore about them. The seminal work on the subject by Iona and Peter Opie was published in four comprehensive volumes covering schoolchildren’s lore and language, games in street and playground, singing games, and games with things. These nicely illustrate the scope of this heading. Most adults will have memories of such things, if only of their favourite counting-out rhyme.

The Opies’ work was mainly undertaken in the 1950s and 1960s, investigating contemporaneous activities and beliefs using a network of school contacts throughout Great Britain, combined with their own fieldwork. They also gathered information from earlier sources. Their methodical research revealed numerous national patterns as well as more localised child-lore. It is interesting to see how Nottinghamshire fares in their national distribution maps – for instance their ‘Mardy Baby’ map and maps showing the distribution of truce terms and the names used for chasers in games.

If there is a down side to the Opies’ work, it is that it has tended to overshadow other work. To some extent, people stopped collecting information because they felt it had all already been done. This is unfortunate, because from the latter end of the 20th century children’s activities have been undergoing a major metamorphosis, fuelled by a mixture of alternative screen-based entertainments, and parental concerns about road safety and child protection. Anecdotal evidence suggests that there has been a marked decline in playground and street games, to the extent that some schools are bringing in people to re-teach them. However, this is an area that is ripe for new research, and in fact a new survey was started in 2007 (see below).

Opies aside, there are many other sources available on child-lore in Nottinghamshire. The earliest of these is Francis Willughby's Book of Games – a manuscript treatise of sports, games and pastimes compiled in the 17th century. While this covers the games of all age groups, many of them were specific to children. Elsewhere, recollections of childhood activities frequently occur in personal memoirs, whether in books, letters to newspapers, essay competition entries, or oral history recordings. These often give details of games and practices that seem to have disappeared from the current children’s repertoire such as Tin Can Alurky or the seasonal changeover of toys in spring and autumn.

The following skipping song was recorded in the playground of Warsop Vale School in 1971:

Wind the wind the wind blows high, The rain comes tumblin’ from the sky, She is handsome, she is pretty, She is the one from the golden city, She goes a courtin’ Wayne Holmes, [name shouted] Please will you tell me who she’ll be.

[The name was changed according to the whim of the singer.]

(M.E.Millington Collection)

A new survey of child-lore entitled Lore of the Playground was initiated in 2007 by the well-respected folklorist Steve Roud, who is aiming to publish a sequel to the Opies’ work in 2009.

Beliefs and the supernatural

To a lesser or greater extent, we all have our store of proverbs and sayings. Perhaps we know of sure fire cures for warts or other ailments that we would never hear from a qualified doctor. Some of us might carry a lucky charm or even admit to being superstitious, although we might otherwise regard ourselves as rational people – or maybe we try to justify our superstitions as rational. There is some logic in not walking under ladders because of the risk of falling objects from whatever activity is taking place at the top. On the other hand, the propitiousness of a black cat crossing your path is difficult to rationalise, especially since opinion seems to be evenly split as to whether this is a sign of bad luck or a sign of good luck.

Nowadays, many of these beliefs are found nationwide, if not internationally. Local variations were recorded by Nottinghamshire antiquarians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for instance in the compilations of Messrs. Cornelius Brown and John Potter Briscoe, and within the pages of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Notes and Queries. The following example quotes Thomas Ratcliffe:

“Complaining one day to a Notts. young lady of the twinges of my enemy was then giving me, she said ‘Always keep in your pocket a double [hazel] nut, and you will never be troubled with toothache.’ She gave me a double nut a few hours afterwards, which I put in my pocket, and --. Of course the toothache went. I still wear the double nut, but will reserve to myself all further remarks as to its efficacy in prevention, for I do not wish to discourage your readers who may be inclined to try.”

(C. Brown, 1874, p.54)

Witchcraft in Nottinghamshire has a mixed history. Trials of witches took place in the county around 1600, as they did elsewhere, mainly in the 17th century. These local witches are, however, under-researched.

More recently, in the 1990s we had the scandal of accusations of Satanic abuse of children in Nottingham. This was part of a national phenomenon that became a cause celèbre in the popular press. Official inquiries concluded that no such abuse had taken place, and that the accusations were a result of communal hysteria and overzealous credulity on the part of the social workers concerned. These events have spawned a number of academic sociology studies.

Even though the accusations of Satanic abuse thankfully proved to be unfounded, there are witches in Nottinghamshire today, arising from a resurgent interest in Paganism. However, their rituals and activities are largely modern inventions of no practical harm. No doubt they may offend some Christians and members of other religions on theological or ideological grounds.

Stories of ghosts and other spectral beings continue unabated. Indeed, there are people who make part of their living from writing about ghosts or conducting ghost walks for tourists. The formulaic nature of these productions and publications tempts one to regard them as having little academic merit. However, they tend not just to regurgitate information gleaned from earlier published sources. For instance, in the case of the prolific writer of ghost books, Rupert Matthews, he has usually visited the places that are alleged to be haunted and updated the stories of apparitions and their background stories from the current residents or people who work there. There is an interaction at play here. The people in the ‘ghost industry’ are certainly perpetuating existing ghost stories, and this often suits the purposes of many a tourist attraction – practically every centuries-old pub or inn, and stately homes such as Newstead Abbey (which has its White Lady and Black Friar ghosts). On the other hand, it is possible that some “witnesses” have talked up if not made up stories for the benefit of investigators.

Folklorists have identified a number of generic types of apparition. One is the ‘Black Dog’ that appears alongside travellers on the road. There are a couple of cases recorded for Nottinghamshire, one from the Worksop area (Rice-Heaps, 2002, and the following from South Muskham:

“... A manuscript dating to 1952 in Nottingham County Library records the words of Mrs. Smalley who was then about 75 years old. 'Her grandfather, who was born in 1804 and died in 1888, used to have occasion to drive from Southwell to Bathley [near South Muskham] in a pony and trap. This involved going along Crow Lane, which leaves South Muskham opposite the school and goes to Bathley. Frequently, along that lane he saw a black dog trotting alongside his trap. Round about 1915 his great-grandson, Mrs. Smalley's son Sidney, used to ride out from Newark on a motorcycle to their home at Bathley. He went into Newark to dances and frequently returned at about 11 o'clock at night. He too often saw a black dog in Crow lane; he sometimes tried to run over it but was never able to. One night Sidney took his father on the back of the motorcycle especially to see the dog, and both of them saw it.'”

(Bob Trubshaw, 1994)

Modern folklore

At the start of this introduction I stated that folklore is ongoing and dynamic, and I hope this has been reinforced by the descriptions above. Some folklore is decidedly modern in origin. For instance, chain letters, which share features with oral transmission, first seem to have appeared during the Great War as a Chain of Prayer for the troops at the front, although somewhat similar collecting campaigns were born along with the Penny Post in 1840. Consequently, the Post Office is periodically inundated with unwanted contributions being sent to sometimes fictitious ‘worthy’ causes.

Other new media have also spawned their own new folklore. ‘Xeroxlore’ is a name that has been given to the photocopied joke sheets, cartoons, and inspirational texts that adorn many an office desk or notice board. These are nowadays more likely to be promulgated by email than by visiting colleagues or photocopier technicians. There is nothing unique to Nottinghamshire in these, apart from a few scurrilous if not obscene sheets based on Robin Hood themes.

Urban myths, also called contemporary legends, usually have an international distribution, but often enhance their credibility by being adapted to name local places or people. One such legend is where a young man has been seduced by a gorgeous woman at a nightclub and taken back to her place. In the morning, he wakes up to find he has a neatly sewn-up wound where a kidney has been surgically removed for transplantation, and the girl is nowhere to be seen. I have heard this story told in all seriousness about a particular nightclub in Nottingham (which I think it would be prudent not to name). As often in such cases, I understand that the management had to issue a public denial of the rumour, although I have not yet been able to track it down, so maybe this itself is yet another urban legend.

One of the most recent traditions, which can unfortunately be seen throughout the county, is the erection of shrines at the scenes of road accidents and other tragedies, especially if the incident involved children. They usually include bunches of flowers, often still in their florists’ cellophane wrappings, propped against fences or tied to lamp posts, but may also include stuffed toys, football kit and other memorabilia. These “shrines” seem to have become more common since the death of Princess Diana. News reports on the local television channels often include a shot of someone leaving a bunch of flowers at the scene of the latest tragedy, and no doubt these are helping to perpetuate the practice.

These shrines can be a problem for the relevant authorities. Removing them may be regarded as insensitive, but there comes a time when the offerings decay and become unsightly, and the act of leaving flowers at road accident site can be a hazard itself. Some local authorities have therefore formulated regulations on what is permissible and how long tributes can remain in place.

References

- Edward Dunnicliff (1933) Correspondence. Folk-lore, Dec. 1933, Vol.44, No.4, p.420

- Frank E. Earp (1996) The Wise Men of Gotham, At the Edge, 1996, No.1 [Available online at: www.indigogroup.co.uk/edge/Gotham1.htm, Accessed 7th July 2007]

- M.E.Millington Children’s Songs from Warsop Vale School. Leeds Archive of Vernacular Culture, 1971, Ref. LAVC/FLF/16/2/2. Copy: Nottingham Local Studies Library

- ‘North Notts.’ (1887) Harvest Customs in Notts., Newark Herald, 3rd Sep.1887, No.792, p.5a

- Victoria Rice-Heaps (2002) Black Shuck Seen, Fortean Times, Jan.2002, No.154, pp.52-53 [Available online at: www.roadghosts.com/Cases%20-%20Other.htm, Accessed 3rd May 2008]

- Bob Trubshaw (1994) Black Dogs in Folklore, Mercian Mysteries,Aug.1994, No.20 [Available online at: www.indigogroup.co.uk/edge/bdogfl.htm, Accessed 3rd May 2008]

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Anne Cockburn and Simon Fury for their comments on and suggestions for this guide, and Paula Blackman for proof reading the draft.