Overview

The religious landscape of England was to change profoundly over the course of the seventeenth century as a single state church was to first be challenged and later fragment into a number of dissenting churches. The county of Nottinghamshire was not only to be a microcosm of this development, but also over the course of the century contribute much towards its progress as it both generated reforming leaders and was also visited by many of the significant personalities of the emerging denominations.

The archdeaconry of Nottingham

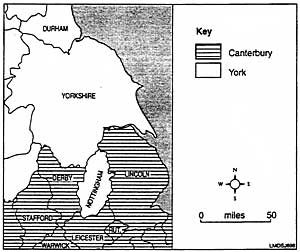

Nottinghamshire, surrounding counties and Ecclesiastical Provinces of York and Canterbury.

The archdeaconry of Nottingham lay on the remote edges of the see of York and consisted of the whole of Nottinghamshire except for 36 parishes, the majority of which were in the ‘Peculiar of Southwell.’ The distance between Nottinghamshire and the city of York meant that it was granted a semi-independent jurisdiction. It had its own distinct Consistory and Correction courts, the records of which still exist in large quantities for the seventeenth century. The existence of a Consistory court in Nottingham gave local officials greater control over the archdeaconry. It also spared litigants having to travel to York to pursue a case, and meant that a small number of lawyers were resident in and around the town. Cases that involved complex legal issues often went straight to York, as did all appeals. The evidence suggests that most social classes within the county were willing to use the local courts by the seventeenth century. Defamation cases, tithe disputes and the licensing of schoolmasters all fell within the brief of the local court. The court also appeared to have an independence that allowed it to commute penances and collect the fines without the direct authorisation of the archbishop. Yet local officials were left in no doubt by the authorities at York that it was the archbishop who had the final say in matters of contention. It was only during a diocesan visitation that the activities of the archdeaconry court ceased.

An outcrop of Mercia sandstone, amounting to an area of 240 square miles laying to the north-west of the river Trent created a soil that was dry, light and generally of poor quality where only gorse and bracken thrive. As a result only small, independent settlements and hamlets could be established here and during the Middle Ages the region became the royal hunting ground of Sherwood Forest. Many of these settlements were far removed from the immediate reproachful eye of either parson or squire and coupled with the vagaries of ecclesiastical jurisdiction (see below) they proved to be receptive to new religious ideas that were brought into the county along the main communication highways of the Great North Road and the river Trent.

Another of the factors that probably helps to explain why religious dissent was able to thrive within the county, especially north of the river Trent, was that the county was surrounded on three sides by the see of Canterbury. Thus to cross the county borders into Leicestershire, Derbyshire, or Lincolnshire not only took you into another parish and county, it also took you into a different ecclesiastical Province. The amount of additional work required of the officials to transfer cases from one ecclesiastical jurisdiction into another probably meant that many minor offences were overlooked if the accused had moved across the border. Thus the remoteness of centralised authority, coupled with the constant passage of commerce, left the archdeaconry vulnerable to the establishment of new religious ideas.

Early history of Puritanism in the county

The origins of Puritanism within the county, as also that of Protestantism, are shrouded in obscurity. As early as the fifteenth century, Professor A. G. Dickens identified north Nottinghamshire as possibly one of the active centres of Lollardy in England but it was in the sixteenth century that the radically new ideas of Protestantism really become established within the county.

Babworth parish church.

By the time that James I ascended to the throne of England in 1603, Puritanism had become well established in a number of the northern parishes of Nottinghamshire. The parish of Scrooby, later to become a centre for separatism, had experienced a succession of puritan curates over the reign of Elizabeth I. Six miles to the south, Richard Clifton had been installed at the living at Babworth in 1585. Writing much later William Bradford, the governor of the Plymouth colony, described Clifton as “a grave and reverend preacher.” Richard Bernard, a Puritan whose writings were to bring him to national attention, was installed at the large parish of Worksop, which lay only 12 miles to the south-west of Scrooby. One of the most prominent of Elizabethan Puritan preachers, Thomas Toller, was at Hayton in 1588 and served as a preacher and lecturer to the surrounding neighbourhood until his move to Sheffield in 1598. James Brewster, brother of the Pilgrim Father William, was vicar of Sutton-cum-Lound from 1594 until his death in 1614. Scrooby was a chapel of ease to the parish of Sutton-cum-Lound, though served by a separate curate. This gathering of Cambridge educated clergy, often related by marriage as well as religious sympathies, created across much of north Nottinghamshire a network of support for zealous Protestants in the region.

Puritans all agreed that the reformation of the state church had not gone far enough, in accordance with their understanding of what the Bible taught, for it still retained a Catholic structure and ritual. Many hoped that the on-going reform could happen from within and that there would not be a need to fragment the one English Protestant church. The ascension to the throne in 1603 of a theologically astute Protestant prince in James I raised expectations of further reforms. At first the new king listened to the petitions of the Puritans and made a number of minor concessions but more importantly commissioned the production of a scholarly and authorised English translation of the Bible for use in churches. It was the publication of the new ecclesiastical canons towards the end of 1604 and, in particular, the second article which stated that the Book of Common Prayer “containeth in it nothing contrary to the word of God” and ordered all ministers to observe in worship both its use and the accompanying rubric that was to cause dissension. Enforcement of this article by the church courts was to cause consternation and eventually fragment the fragile Puritan consensus. Many sought to find ways to avoid or circumscribe actions such as kneeling for communion or bowing at the name of Jesus, as neither had Biblical warrant or sanction. For more extremist Puritans these canons proved that the Church of England was unredeemable and gave no choice but to separate completely from it. At Scrooby in north Nottinghamshire such a separatist congregation formed and collaborated closely with a sister congregation just 11 miles away in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. Links of kinship and shared ecclesiology cemented this relationship.

The Separatist Experiment and the Pilgrim Fathers

The early establishment of Puritanism in Nottinghamshire suggests that the potential for separatism was not a phenomenon introduced into the region with the arrival of John Smyth and John Robinson but was always there. In fact, both of these leading separatists were born in Sturton-le-Steeple in north Nottinghamshire and spent their formative years here before going on to the University of Cambridge. It may have been their acquaintance with the region’s more zealous Protestant families that persuaded them to return.

In 1604, four Nottinghamshire Puritan clerics (Richard Bernard, Richard Clifton, Robert Southworth and Henry Gray) were deprived of their livings for refusing to subscribe to the new canons. Unlike Smyth and Robinson, however, they remained close to their former parishes and through the gentle mediation and persuasion of Archbishop Tobias Matthew both Bernard and Gray were persuaded to conform in 1608. In contrast, Smyth and Robinson moved some distance away from their initial pastoral/lecturing livings so as to avoid further harassment and to further their vision of forming separated gatherings of godly congregations.

Sometime before 1604, when he was reported to the authorities for unlicensed preaching, Smyth founded a congregation at Gainsborough in Lincolnshire, which met at the home of the Hickman family in the Old Hall. One of its earliest members was Thomas Helwys of Broxtowe Hall, near Nottingham, who was also a close friend of Richard Bernard and sought to act as an intermediary between Bernard and Smyth until the former's return to the church at the start of 1608. Also attending by the end of 1604 were William Brewster and George Morton of Scrooby, William Bradford of Austerfield and John Robinson from his family home at Sturton as well as numerous “small farmers and labouring people” who travelled from across Nottinghamshire.

![A Presentment Bill of 1598 relating to Scrooby including the line: 'William Bruster [Brewster] for repeatinge of sermons publiquelie in the churche w[i]thout authoritie for anie thinge theie knowe'. Image courtesy of Manuscripts and Special Collections, The University of Nottingham (ref: AN/PB 292/7/46)](../images/themes/nonconformity/brewster-presentment-bill.jpg)

A Presentment Bill of 1598 relating to Scrooby includes a presentment of William Brewster "for repeatinge of sermons publiquelie in the churche w[i]thout authoritie for anie thinge theie knowe." Image courtesy of Manuscripts and Special Collections, The University of Nottingham (ref: AN/PB 292/7/46)

The year 1605 was to be of significance for Nottinghamshire as around this time William Brewster allowed his home to become a meeting place, so making unnecessary the long round trips to Gainsborough. According to William Bradford (1590-1657) by autumn 1606 the congregation consisted of between 50 to 60 people and it was at this time that they made the decision to separate completely from the established church with Robinson becoming the pastor, Clifton the teacher and Brewster ruling elder. Richard Bernard established another group at Worksop around the same time, but unlike the Scrooby congregation this remained firmly within the established church.

William Bradford’s account of the early events at Scrooby, written in 1630, provides us with an interesting insight into the characters of William Brewster and John Robinson; of Brewster he wrote:

"He lived . . . . in good esteem among his friends, and the good gentlemen of these parts, especially the godly and the religious. He did much good in the county where he lived in prompting and furthering religion."

The deep affection held for John Robinson is also conveyed through Bradford’s account:

"He was very courteous, affable and sociable in his conversation, and towards his own people especially. He was an acute and expert disputant, very quick and ready, and had much bickering with the Arminians, who stood more in fear of him than any of the universities."

Over the period 1607-1608, the two congregations at Gainsborough and Scrooby grew apart and became distinctive churches. John Smyth and John Robinson were beginning to disagree about several theological matters, including the issue about the authority elders possessed. Prior to 1609 these theological differences were still only minor ones, and geography may have played as important a part in the evolution of the two distinct congregations as any other issue but once in Holland the differences escalated into major disagreements.

Prior to 1607 the ecclesiastical authorities appeared to be uninformed about the separatist congregation but in that year they instigated proceedings at the report of local residents. Gervase Neville of Scrooby was cited in November for “his disobedience and schismaticall obstinacie.” The following month Richard Johnson, William Brewster and Robert Rochester, all of Scrooby, and Francis Jesson of Worksop were all cited for separatist activities. As the pressure to conformed increased the congregation increasingly began to look towards fleeing from the persecution and by September 1608 Brewster and the Scrooby congregation had followed that of Smyth’s at Gainsborough into exile in Holland.

The shaping of Nottinghamshire Puritanism, 1610-1642

Although a number of north Nottinghamshire Puritan families had links with the separatist congregations, the majority of them did not emigrate with their more zealous kinsfolk; William Bradford asserted that only 125 individuals actually fled. Families such as the Denmans of East Retford remained behind and continued to incur the ire of the ecclesiastical authorities, although their son Humphrey was living in Amsterdam by 1634. Under the supervision of Michael Pufrey, a deputy of the archdeacon, a more relaxed approach was taken towards moderate Puritans who kept a low profile.

Persistent offenders, who constantly flouted the rubric of the Prayer Book were hauled before the courts. Men such as Hezekiah Burton, vicar of Sutton cum Lound, although cited on five separate occasions for puritan activities, still managed to remain in his living until his death in 1646. A number of other Puritan clerics were also cited over the 1620s but their skill at brinkmanship meant that none of them were deprived of their livings. Around such individuals gatherings of zealous Protestants tended to gather for bible study and prayer.

Over the years 1610-1629, 101 lay persons were also presented to the church court, predominantly for refusing to observe the more catholic traditions of the Prayer Book rubric such as kneeling for communion or bowing at the name of Jesus or for ‘sermon gadding’ (going elsewhere to hear preaching ministers) or not attending midweek Saint’s or Holy Day services. The majority of these cases (63%) occurred over the years 1620-1629, suggesting that the more zealous forms of Protestantism did not disappear with the separatists but continued to develop and find new adherents.

The 1630s were to witness across the county an increasing desire amongst the laity to hear sermons but this at a time when the new archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, sought to control the number of preachers and lecturers and enforce greater ceremonial observance at parish level. As one local Puritan observed when a preaching minister was moved from his living: “God . . . . . hath taken away your good minister from you, and placed a dum dogge in his room.”

In the county town of Nottingham there had been a long tradition of parishioners moving between the churches of St Mary’s and St Peter’s, depending on whichever one was having a sermon preached on the Sunday, but during the latter part of the 1630s increasing numbers of individuals were cited at the courts for so doing. The perceived vindictiveness of the authorities against those who wanted to do no other than hear godly preaching raised the angst of many who would in no way have identified themselves with the label ‘Puritan.’ In many ways Nottinghamshire reflected the growing anger across the county to what was increasingly seen as innovative and intrusive religious legislation. National events over the period 1640-1642, which culminated in the breakdown of censorship and the dismantling of High Commission and the church courts, facilitated an outpouring of Protestant zeal and preaching across the county but over the next 20 years what was to become increasingly clear was that there was no universal consensus about what a reformed congregation should believe or how it should be organised.

“When women preach and cobblers pray:” Civil war and the establishment of Nonconformity across Nottinghamshire

Colonel John Hutchinson

With the breakdown of Anglicanism after 1642, new ways of structuring Protestant churches began to manifest themselves. Within the county town, the majority of puritans favoured in practice a Presbyterian form of church government. To the ‘natural rulers’ this was viewed as a compromise between both the need for a national church and yet at the same time greater freedom for the local congregation. The establishment of a major Parliamentarian garrison at Nottingham castle, under the command of Colonel John Hutchinson, and the constant passage through it of large numbers of soldiers and their chaplains from across the country, facilitated a more tolerant attitude towards the religious activities of some of the soldiers. This was to become a source of considerable friction between the town and the governor both throughout the war and beyond it. Our main source of information about this friction is the somewhat biased but detailed biography of Colonel John Hutchinson written by his wife, Lucy.

In 1644, matters came to a head in Nottingham when it was discovered that some of the gunners at the castle were holding religious meetings in their chambers. At "the instigation of the ministers and godly people" of the town, the conventicle was broken up and certain religious tracts against paedo baptism were confiscated. These men had proved to be loyal soldiers to Parliament and as the war was still waging, Hutchinson was unwilling to sacrifice them to his Presbyterian inclined opponents. He therefore released them from arrest because

"though of different judgements in matter of worship, (they) were otherwise honest,

peaceable and very zealous and faithful to the cause."

For this action, the Colonel was to be marked out as a “favourer of separatists.” The presence of Cromwell’s regiment at Nottingham castle in 1643 and again in 1648, enabled the local garrison to encounter a variety of religious ideas. Amongst his troops there had long been a tradition of religious exploration, aided and abetted by religiously zealous army chaplains. The small congregations of Familists and Baptists recorded in the town in 1669 probably had their origins in this period.

George Fox

In 1647 the founder of the Quakers, George Fox, recorded in his journal a first visit to north Nottinghamshire and in the following year he noted that around the Mansfield and Skegby areas “there was a great meeting of professors and people.” Surviving testimony from eye-witnesses such as Fox suggest that such groups of religious experimentalists, now no longer constrained by ecclesiastical or civil legislation, were prevalent across much of Nottinghamshire. The subsequent congregations of Presbyterians, Quakers and Baptists identified in Mansfield and Skegby in 1669 may well have had their origins in such gatherings of religious seekers as identified by Fox.

Of all the Puritan groups within the county during the 1650s, the Presbyterians were the most numerous and influential, especially within Nottingham. They were, of religious practice, the most conservative of all the groups. Although they had rejected episcopacy, they sought to replace it by an even stronger, oligarchic form of church government. During the 1650s, they were at the vanguard of the movement to create a more “godly society.” Sabbath observance, the provision of godly lecturers and preachers, and the willingness to use the law courts to achieve this new society were all characteristics of this period. The arrival of ministers John Whitlock and William Reynolds to St Mary’s, Nottingham, in 1651 witnessed the establishment of a Presbyterian form of government there with elders and deacons. In 1655/6 a Presbyterian classis was established to which, over the next four years, 22 parishes in and around Nottingham subscribed and which has provided Nottinghamshire with one of only a few nationally remaining sets of meeting minutes.

Nottinghamshire was also an important centre for the development of Quakerism in the 1650s. The founder, George Fox, began his early ministry in Nottinghamshire and many of his early converts in the region went on to become preachers and ministers in the movement. Two of these, Elizabeth Hooton of Skegby and James Parnell of Retford, were figures of national importance, though Parnell suffered an early martyr’s death at Colchester in 1656.

By the time of the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 and the subsequent Act of Uniformity in 1662, which sought to re-establish a single national Anglican church, the newfound independent congregations were too well established across Nottinghamshire to be extinguished by legislation. Even so, 38 Nottinghamshire clergy were deprived of their livings for refusing to conform in 1662, though seven of these did later conform.

Nonconformity established

In July 1669, the Archdeacon of Nottingham issued a questionnaire regarding illegal Conventicles (religious gatherings) to his clergy. This was in response to a special directive from the king and his Privy Council, and authorised by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. This more than any other survey was to show just how well established the evolving Protestant denominations were across the county. These returns clearly show that whilst the town of Nottingham was the centre and base for Presbyterianism and Independency, its significance for the Quakers and Baptists was not so pronounced. Within the county town, seven Conventicles were identified, two of which were Presbyterian with an attendance of 400 to 500 between them. Thus over half of the county’s Presbyterians were located in Nottingham.

The next largest group were the Independents, whose one Conventicle attracted 200 persons and this congregation went on to become the Castle Gate Congregational Church after 1689. The Quakers in the county were more firmly established in the rural parishes around Mansfield and Skegby but this was to leave them more exposed to identification and persecution and it is not without significance that many of the county’s leading Quakers emigrated to north America after the establishment of Pennsylvania in 1681. This left the remaining congregations much diminished by their absence.

In many ways the century ended as it began with a tale of migration to the Americas, and Protestant Nonconformity, which although established, was still a relatively small phenomenon in numbers, though certainly not in influence. Not until the arrival of Methodism at the end of the eighteenth century was this to be reversed.