|

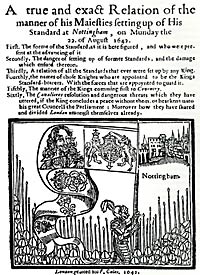

Cover of a Parliamentarian tract on the raising of the King's Standard at Nottingham in 1642. |

It is generally accepted that the civil war began in Nottingham on 22 August 1642 when King Charles I had the royal standard flown within the precincts of the castle. This act symbolised the failure of political efforts to reconcile the differences between the majority of the political world represented by parliament and himself and his smaller group of supporters. However, by this time the British Isles had been wracked by rebellion, war and revolution for three years and England itself had been the site of fighting and subjected to military occupation that had ended only a year previously, so the claim for a Nottingham start date is quite difficult to argue.

After the relative peace of the 1630s, the wars of the 1640s overwhelmed Nottinghamshire as they did the rest of the British Isles. The ‘thirties had been only been superficially quiet: a range of problems were like the undercurrents of a river, at times unseen, but always present. Anger at Charles I’s non-parliamentary taxation policies was seen in the streets where officials were defied and attacked and in the courts where defaulters were presented in unprecedented numbers and Newark tried to pass part of its allocation out into the rest of the county. The king’s religious reforms caused dissent which was rarely vocal, but marked by small acts of disobedience such as sermon-crawling to hear different ministers. In themselves these acts of protest were not enough to bring about civil war, but when the English-Welsh state collapsed at the centre as a result of wars in Scotland and Ireland, they acted as fractures along which government and society broke open. Lucy Hutchinson, whose biography of her husband John Hutchinson of Owthorpe, parliament’s governor of Nottingham, gives us the most comprehensive account of Nottinghamshire’s war saw this clearly: ‘Before the flame of the warre broke out in the top of the chimnies, the smoake ascended in every country’.

Nottingham became embroiled in early factional posturing during the summer of 1642. The king visited the town on 21 July on his tour of the Midlands; he visited again a few days later having failed to get hold of Leicester’s county magazine. It was essential for the king and parliament to gain ammunition. The major national stock of weaponry was normally held in the Tower of London but some was stored at Hull where it had been sent during the Bishop’s Wars (1639 and 1640). The king tried to seize this in April 1642 but had been refused access to the port. The only other munitions in England were stored in county towns to supply the county-based part-time force: the Trained Bands. Nottingham had a store in the Town Hall at Weekday Cross. In the wake of his second visit, Charles sent his lord lieutenant (commander of the trained bands) Henry, Lord Newark and county high sheriff John Digby to get it. Parliament’s rival lord lieutenant the Earl of Clare was out of town and so John Hutchinson and the mayor were asked to stop Newark. The four men argued in the town hall, with an angry and frightened crowd outside shouting encouragement to Hutchinson. In the end the men reached a compromise, placing two locks on the store with one key held by high sheriff Digby and the other by the mayor John James. In the end however royalists simply broke the door down with an axe on 19 August, just before the raising of the standard. The king meanwhile was further south trying to get his hands on the Warwickshire munitions at Coventry. He returned northwards empty handed and made a stand at Nottingham, raising the royal standard in the castle precincts on the 22nd August. Charles appeared to be short of troops and this has been used by some historians as an indication of the unpopularity of his cause. In reality many of his troops were still scattered around the midlands and those at Nottingham represented about three quarters of the county’s Trained Bands all that could be called together at very short notice. Almost immediately the war shifted focus southwards, after the king marched initially westwards to join with the large scale recruitment programme being organised on his behalf.

|

The gatehouse at Newark Castle (photo: Martyn Bennett). |

During the initial campaign of the war which witness the battles of Edgehill (23 October 1642) and Brentford (12 November 1642) and culminating at the stand-off at Turnham Green (13 November 1642), Derby was seized for Parliament by Sir John Gell who then lent troops to John and George Hutchinson to enable them to take control of Nottingham. In order to prevent a complete meltdown in the Midlands, a Scottish professional soldier Sir John Henderson was sent to help royalist Sir John Digby take over Newark and from them on the county was polarised around these two rival garrisons. Nottingham was strategically less important than Newark, but it was the site of county government and an important trade centre, which could offset Newark’s value as a strong point in the Great North Road. Newark’s importance was quickly recognised and in February 1643 Major General Thomas Ballard attacked the town with a collection of forces drawn from the region, including Hutchinson’s men from Nottingham. The siege failed and was followed by recrimination amongst the parliamentarian commanders; but it was not long before Newark was targeted again because of its place on the Great North Road.

In February Queen Henrietta Maria had returned to England with money and ammunition she had gained on the continent by pawning some of the crown jewels. By May she was ready to go southwards with a newly recruited army and an ammunition train. This involved passing through Newark and parliamentarians drew forces together from Hull, Nottingham and East Anglian troops under Colonel Oliver Cromwell. The plan to seize Newark came to nothing as the Hull commanders were secretly negotiating with the royalists in the north and the alliance collapsed as the queen marched southwards and the parliamentarians withdrew. The queen stopped at Newark from where she launched an attack on Nottingham on either the 21st or 23rd of June. On 3 July the queen’s army left Newark and progressed via Ashby de la Zouch to join the king in the south Midlands. The summer of 1643 marked a low point in Nottinghamshire parliamentarian fortunes with a ring of garrisons established by the royalists across the region. However despite the presence of a large royalist force under the Marquis of Newcastle in the north of the county, Nottingham castle remained impervious to attack and treachery. The most severe test was in September when for five days from 18 September the town was occupied by royalists. The attackers established at fort at Trent Bridge, thus for the first time opening a route into southeast Nottinghamshire for their tax collectors: they held it for a month. The region was further hemmed in by royalist garrisons until the beginning of 1644.

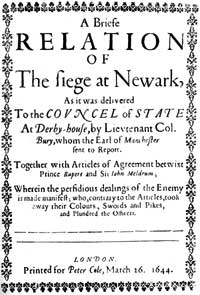

In January 1644 the Scots who had become allies of parliament in the previous year sent an army into northern England. Royalist forces were drawn from Nottinghamshire to go northwards to join in the attempt to halt the Scots’ advance. This weakening enabled the local parliamentarians to become more active. Even so there was another attack on Nottingham by the local royalist commander Lord Loughborough and troops from Newark in January. A thousand royalists occupied the town and another thousand cut the town and castle off from all outside help. Again this lasted several days, but the castle stood firm. During the following months it was Newark that was besieged by forces from across the region gathered by Sir John Meldrum. The town was ringed by about seven thousand men, and large patrols were sent out to keep local royalist forces in check. Lord Loughborough summoned help from Prince Rupert, based in the West Midlands who sent forces to join the attack on the besieging force. After fighting in north Leicestershire in mid-March, Loughborough’s forces, alongside Rupert and his reinforcements, marched on Newark where in the early hours of 21 March 1644 they attacked Meldrum. The battle of Newark was fought chiefly on the east side of the town, but the parliamentarian were quickly driven back to a position north of Newark, around the Spittle where the Earl of Exeter had a large house in the grounds of a former religious hospital. Retreat across the island in the Trent was prevented when the bridge at Muskham was captured. Meldrum surrendered.

|

Pamphlet on the siege of Newark, published in March 1644. |

The victory at Newark was important, it re-established royalist control in the county and nearby regions, but it underlined an important point: royalist success in the area could only be achieved with outside help, particularly after the Scottish invasion had removed much needed troops from Lord Loughborough’s command. The tenuous nature of the royalist hold was underlined in the summer when yet more troops were taken out of the region to march northwards with Prince Rupert. Following the defeat of Yorkshire royalists at the Battle of Selby (11 April 1644) the Marquis of Newcastle had retreated from the north east, where he had been holding back the Scots, to York where he had become trapped. Prince Rupert was to march north to his rescue. The prince drew yet more of Loughborough’s regiments northwards including the Nottinghamshire horse from Newark under Major General George Porter. The royalist horse from York had also camped in Nottinghamshire for several weeks whilst the rescue effort was being assembled, and this had proved a severe drain on resources. This would have been a survivable situation had not the combined armies of Rupert and Newcastle (with several of Lord Loughborough’s and Newark regiments alongside them) been defeated at the Battle of Marston Moor (2 July 1644). The defeat led to the collapse of the royalists in the north and then, domino-like, to the fall of the royalist north Midlands. In Nottinghamshire Welbeck House fell to parliament; royalists were left to hold only the Newark outposts at Shelford, Thurgarton and Wiverton.

In October Newark forces were involved in the defeat of Loughborough’s army at the Battle of Denton, which further inhibited the royalists’ power in the region as a whole. The garrison at Newark, whose governor Sir Richard Byron was replaced by Richard Willys, became less able to collect necessary taxation in Lincolnshire and even in its Nottinghamshire hinterland. There was however, a renaissance of royalist fortunes in the spring of 1645 and Newark forces were able to flex their wings again. In the summer Newark forces were involved in the king’s march into the north Midlands and as a result were present at the capture of Leicester on 31 May and then in the Battle of Naseby (14 June 1645). At Naseby the Newark Horse were swept from the field by Cromwell’s attack on the royalist left flank, suffering casualties that limited the garrison’s effectiveness again.

|

Plaque on The Governor's House in Newark (photo: Martyn Bennett). |

The final stages of the conflict saw a war of attrition in Nottinghamshire. The king was present in the county during late August 1645 contemplating a march north to join his successful commander in Scotland, the Marquis of Montrose, and again in October. Charles’s presence allowed some royalist initiatives and Welbeck was once more established as a garrison by troops from Newark (although they were actually Derbyshire forces) and Newark was able to collect tax from Lincolnshire again. In October Newark witnessed the dramatic meeting of Charles and his nephew Prince Rupert who was effectively cashiered for surrendering Bristol the previous month, and his friend Richard Willys was replaced as governor of Newark. The king marched out of the region in late October as the Scots and North Army closed in, capturing Shelford and Wiverton (Welbeck also surrendered), by the end of November Newark, with its impressive fortifications built largely after the second siege, was surrounded. The third siege of Newark by the Scottish army of Lord Leven and the English Northern Army under Sydenham Pointz lasted until 6 May. The townspeople and garrison suffered from almost complete isolation and no relief attempt could be made to help them. Although the town might have held out longer the siege was brought to a dramatic end when the king arrived suddenly at Southwell and surrendered to Lord Leven in the hope of driving a wedge between the Scots and parliament. This political act failed at this point (although it would work out in the long term) and the immediate surrender of Newark was demanded by his English and Scottish captors the siege and effectively the war in the county ended in 6 May 1646. The dismantling of the massive earthworks around the town was begun almost immediately, but ended quickly when a series of diseases broke out in the town, making it dangerous for the workers to stay there: many thereby remain to this day.

Nottinghamshire witnessed little action in the second civil war which began partly because the king was eventually successful in dividing his enemies. A few local royalist activists were defeated at Willoughby Field during the summer months and some of the captured Scots and English royalists were held at Nottingham Castle. In the wake of the war, England and Wales became a free state and the trappings of war like Nottingham Castle were destroyed to prevent them being seized by royalist insurgents.