In the not too distant past Nottingham had shopping outlets leading from every compass point into the heart of the city meeting at the Old Market Square. The city was considered opulent by some, with a several industries, including Players, Raleigh and Boots providing lucrative sources of income to be spent in these shops. As such the city boasted a number of quality retail Department Stores at the turn of the twentieth century. Many of these were centered around the Old Market Square. Shops such as Pearson Brothers, Burtons of Smithy Row, Tobys and Griffin and Spalding were all well known stores until the development of the shopping malls of 1980s when the Broad Marsh and Victoria Centres were developed and took shopping away from the Square into what was then the new way of shopping.

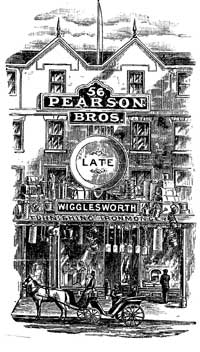

Pearson Bros. Ltd

Pearson's first shop, c.1894 (image courtesy of The Nottinghamshire Historian).

Pearson Bros. of Long Row was not the first major department store but until its demise in 1988 it was certainly one of the most iconic in the city, with its Georgian facade facing Long Row and the very modern Scandinavian entrance on Upper Parliament Street. However, it began life in a small ironmongery and silver plate shop at 56 Long Row when Frederick Pearson bought the premises for his two sons, Charles William and Tom in 1889. This address remained for the rest of the company’s history. The original staff comprised of Frederick Pearson and his two sons, a porter and a boy. As well as the shop front there was an office and a cellar with a pump in the backyard for washing in. Pearson senior could not have foreseen that the shop would one day be among the city’s leading stores.

In 1894 when electricity first began to be installed in private houses the brothers began to expand the store and engaged an electrical engineer and contracts were given for wiring and fittings – a side of the company which was developed even further with the sale of electrical appliances, such as table lamps and wirelesses, in the store. In 1898 with an increasing stock it was necessary to extend the store, the first of many such extensions. A showroom was built at the back of the store especially for the newly designed firegrates which the company began to develop and sell. Over the next three decades more premises adjacent to the store were purchased and the store expanded and sold “everything for the house” and a bit more! Goods such as bedding, fireplaces, china, pianos, garden tools, jewellery, records, radios and later televisions could be purchased in the store.

Stoneware jar from Pearsons (image courtesy of Nottingham City Museums and Art Galleries).

During the period when the Council House was being built in the late 1920s trade fell off for all the shops surrounding the Market Square but picked up again and Pearsons opened another extension to their premises in May 1931. They purchased their first second-hand van for £300 around the same time this would be the first of a fleet of delivery vehicles. The audition room for listening to gramophone records became a café and in 1940 they purchased a music business from next door.

The shop went out of its way to impress customers and attract as many people as possible. In 1933 the shop had a theme day of an Indian Village, with staff performing magic tricks. Laurie Pearson, son of Tom Pearson invented and patented the first practical and safe electric blanket which was sold in the store. It had an old-fashioned lift custom fitted to cope with the building’s different floors which were odd angles. It had brass panels and an oak door and was operated by one man for many years.

In 1949 the store celebrated its Diamond Jubilee and by 1961 the store had survived 72 years in business with a staff of 360 working in the various departments. In 1966 the Guardian Journal said that the store frontage on Upper Parliament Street entrance was ‘possibly the most imposing store frontage in the city.’ It consisted of a vast expanse of glass 33 feet high, 27 feet wide and weighed three and half tons. The store had a name for quality and service but the management wanted to get away from the old fashioned look of the store so they had visited Scandinavia and was so impressed with the shop fronts there that they decided to emulate them in their own store. In 1986 there was coffee shop and Platters restaurant where the waitresses were dressed in Victorian style outfits. In the same year a £100,000 fashion floor was opened within the store.

Unfortunately time was running out for this store because by 1987 the grandson of the founder was fighting to stop the store being closed and developed into a shopping arcade but by October of that year approval had been given to sell the shop which closed its doors in January 1988 after 98 years, two years short of its centenary, with a loss of 115 jobs. The new owners Grosvenor Properties, London were forced to make major changes to plans for redevelopment of the property which included saving the eighteenth century buildings behind the facade and to include in the scheme the creation of covered courtyards. The buildings stood empty whilst decisions were made but in 1990 the company shelved a £25m shopping development when the retail market collapsed and interest rates started to climb. Grosvenor wanted to demolish the eighteenth century frontage but was thankfully refused.

A further two years saw the building deteriorate and it remained a city centre eyesore after high winds forced the frontage to be shored up. The building was to face yet more uncertainty when in 1993 permission was granted for the development into government offices and a multi-storey car park at a cost £5m which was ‘designed to blend in with the area in terms of scale and design.’ Nottingham Director of Development, Jim Taylor, said he was “‘delighted’… this was a golden opportunity to restore the character of Hurts Yard (within the surrounding area), particularly the new building to Parliament Street which will be one of the most prominent in the city centre.” Nothing could be further from the reality as this area remains an eyesore with boarded up and unattractive shop fronts to this day. The outside is not alone in loosing its character as a disastrous fire in 1996 saw the buildings interior destroyed.

J H Tobys Ltd, Department Store, Friar Lane

Toby’s, Friar Lane, was a distinctive department store with displays of cut glass, china, pottery and gifts which were assured to delight the recipients. It all began when James Hartley, a plumber by trade, and the owner of a modern sanitary fittings showroom on Friar Lane and his wife, who had been involved in the sale of glass and china decided to open a shop in premises next door in August 1929. They called the shop Toby’s, which was the nickname for James. The shop had humble beginnings reselling unwanted wedding gifts, but soon became the sole local distributor of Crown Derby, Royal Doulton and Stuart Crystal china and glassware.

In the 1920s they moved from the small shop at the top of Friar Lane to larger premises, Vernon House, near the junction with the Old Market Square. At that time fifty people were employed by the store. A decade later further property behind the store was acquired for the furniture and household equipment which they were now selling. The shop had prestigious customers, in the Players family (cigarettes), Jesse Boot, and supplied crockery to the University of Nottingham.

In 1937 James died but his wife carried on until 1968 when she too died, aged 81 years. During that time she steered the store through the austerity war years and into the 1950s consumer boom. The shop premises extended backwards from Friar Lane to St James Street and a ladies’ fashion department was now included. Upon Florence’s death the shop was taken over by the Grant-Warden group with James’s nephew, Bob Hartley, as managing director. Unfortunately the opening of the Broad Marsh and Victoria Centres, which essentially took away retail shopping from the Old Market Square, meant the end for several shops in the Old Market Square. In 1982 after a business spanning 58 years, Toby’s closed. The shop did reopen the same year and was linked to a Sussex-based store, Hoadleys, where the shop was broken down into smaller units known as shop-in-shops but the writing was on the wall and in 1983 it closed once again.

Many people have nostalgic memories of the shop; many saying how they remember it being a shop selling expensive items. It had arched windows – which still survive – with red canopies over them and a large Toby Jug was displayed out side over one of the entrances.

Attempts were made in 1987 to open it as a café-bar but the plans were rejected and so the shop stayed closed for many years until it was reopened as a bar called The Approach, in recent years.

Burton’s of Smithy Row

(Image courtesy of Local Studies, Nottingham Central Library).

This store began in 1857 as a flourishing grocery and provision merchant established by Messers Bains brothers on Albert Street, Nottingham and was known as ‘The Times Tea Warehouse’. It was acquired by Joseph Burton in 1886. Burton had been born in 1832 in Winster, Derbyshire, the son of a blacksmith and was apprenticed to a grocer in Winster and experience in London he settled in Nottingham and began his empire as a fruiterer in St Ann’s Well Road. Joseph was aware that for the poor in Nottingham food was very basic but around the Shambles (the area surrounding the Old Market Square) there were 76 butchers, and he saw an opening to expand his business.

At the age of 26 years he moved into 7 Smithy Row (behind the old Exchange Building) which had been Higginbotham’s grocers. Burton changed the name and title and became Provisions Merchant. He later acquired other properties along the row and expanded the variety of produce and allowed customers to taste before buying – a practice which continued right to the end. In 1883 took over Stevenson’s fish, game and poultry shop, which proved to be a clever move as this side of the business became an important section of the later store. In 1885 he acquired important premises on Talbot Street which had a huge cave underneath and was used for a cold storage facility and later set up an ice-making manufacture, the ice being transported by flat backed carts around Nottingham. The headquarters of the firm was established nearby and a fleet of horse drawn vehicles was built to deliver goods to customers.

During the last decade of the nineteenth century the company grew in size and prestige. Joseph’s son, Frank, took an interest in the running of the cold storage and later took on many of the other responsibilities allowing his father time for recreation. Frank had been a keen sportsman and had played for Nottingham Forest and England in 1890 but allowed the shop and his position as a JP and later High Sheriff, to replace these interests. During this time Burton’s had taken over shops in Alfreton, Heanor, Eastwood and Rushden (1896), followed by Coventry and Eckington, near Sheffield in 1898 but were allowed to continue under their own names. New factory buildings, dedicated to jam making, were erected at the bottom of Wollaton Street and employee numbers increased rapidly. Burton’s became a limited company in 1900. Frank was keen to sell wines and spirits, but unfortunately his father was not in agreement and on Joseph’s weekly visit to the shop on Smithy Row, bottles had to be removed!

Joseph died at the age of 85 years in 1916 leaving a flourishing business empire. In his later years he had taken on the role of philanthropist and bought a hall in Winster, his home village, for reading and to be used as a teetotal village hall, and is still at the centre of community today. He also donated to the Nottingham General Hospital.

Another decade passed before Burton’s had the opportunity to move into new premises on Smithy Row. In 1926 the Old Exchange was pulled down and included the destruction of the butcher’s shambles and other properties behind the Exchange. It was another three years before Burton’s moved into their new premises in the new Council House building where they were to remain until they closed in 1983. Burton’s of Smithy Row had now become an icon of Nottingham. Several new departments were included in the modern shop but the fish shop retained an open slab front until after the Second World War. The window displays were legendary and in 1937, the Coronation year, they won the first prize of £5000 in a Daily Mail window dressing display. In 1928 the store took delivery of several Trojan motor vans for delivering goods to customers. The staff worked long hours, 8-6 during the week, 8-7 Fridays and 8-8 on Saturdays for which they were paid good wages.

However the 1939-45 war curtailed the expansion of the store and proved difficult to stock the variety and quality of goods they were renowned for. Earlier closing was introduced and they did not return to the late hours after 1945. The window displays were not as elaborate but this was to change in the 1950s when they began their famous Christmas displays in the Exchange Arcade. To mark the Coronation of Elizabeth II the window displays surpassed themselves with figures of guardsmen in each of the windows. By now the company had more than 200 branches around the country. They were renowned for their foreign produce; frogs’ legs, caviar, poppadoms and cheeses as well as their home baked cakes and pastries and fish from around the British Isles. Throughout the 1950s and 60s ‘Burton’s of Smithy Row’ were almost as famous as Fortnum and Mason, where some produce was purchased. In 1957 there was Burton’s supermarket on High Road, Beeston but goods were still purchased individually and not at a final check-out. In 1958 the company celebrated their centenary.

However, by the late 1960s the arrival of the ‘American’ shopping method of self service, Burton’s was forced to sell its chain of 200 shops to Fine Fare. The Nottingham flagship kept going but factors were working against the shop continuing for much longer, despite efforts in promoting ideas like an Italian food and wine festival in September 1972. The new way of supermarket shopping was beginning to impact on shops like Burton’s and parking around the Council House was increasingly difficult for customers. In 1974 the delivery service was withdrawn and two years later the confectionery and biscuit shop closed.

Despite over a century and a quarter of sales and its popularity in Nottingham the family-run business could not compete with the shopping habits of the new era and on February 5, 1983 the shop closed with the loss of 75 jobs.

The three stores which were at one time such institutions in Nottingham and are remembered with fondness by many people were unable to compete with the Victoria and Broad Marsh shopping centres and the new shopping habits of the late 1960/70s. Despite all three stores offering value and service to the customer they could not survive.

Hopewells the furnishers

Hopewell's removal van, 1922 (image courtesy of Adam Hopewell).

The oldest furniture retailer in the city was established in the late nineteenth century and has moved premises countless times. In 1885 Frank Edwin Hopewell opened a second hand furniture shop at 279 Great Alfred Street Central, Nottingham. Together with his wife, Annie, who he married in 1890, they built up a business which has outlasted many competitors and celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2010.

The couple had eight children and with this many mouths to feed life was a constant struggle. Frank had received no special education or business advice and suffered from ill-health, so he was fortunate in having Annie, who not only brought up the children but assisted in the firm and helped to develop it over the years until her death in 1943. From all accounts she was a formidable woman but not without a soft side; she was known to take in poor children, wash and feed them and send them home in decent clothes.

Although times were difficult for the couple and their ever growing family Frank was known to be trustworthy and creditworthy; the story is retold that he had insufficient funds to pay a Bill of Exchange on Monday, so he loaded his cart up with furniture and drove to Mansfield on the Saturday before, auctioned it off in the Market Place and came home with sufficient money to pay the bank on the Monday. The couple divided the work, with Annie looking after the shop and Frank going out to collect furniture or weekly hire purchase payments with one or more of their children.

The company moved several times in several years to larger premises for their ever expanding business. They moved along Great Alfred Street and then onto St Ann’s Well Road. They lived at the rear of 156 and 158 St Ann’s Well Road for many years, only moving into a separate home some years later. The eldest of their children, Frank, who was a pupil at Nottingham High School unfortunately died at the age of fourteen in the early part of the twentieth century. Two of the younger boys had joined the business on leaving school but with the start of the First World War they joined the many other young men fighting the Germans. Frank and Annie were left to carry on the business but because they had a strong foundation it kept going through the war years. The four remaining eldest boys re-joined the shop from the armed forces and from school. The youngest boy, Bernard, was articled to Nottingham City Treasury and then went on to join a firm of Chartered accountants in Nottingham before going to America for a period of time. He finally joined the business around 1930. He was a prominent member of various furniture and design associations, including being a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of furniture makers in 1963 and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in 1968.

During the inter-war years there was some progress with the company developing a removals business, firstly with horse-drawn drays and eventually using motor vehicles. It went on to become the largest removal company in Nottingham. More showroom space was acquired on St Ann’s Well Road to make room for the growing removals and furniture business. A branch was opened on Radford Road, Nottingham and was managed by Jim, one of the elder sons, but in 1935 he left the parent company and went alone.

In 1936 the business suffered a severe loss when Frank Edwin was killed in a motor accident. Nevertheless the company finally made the move into the centre of Nottingham at 8 and 10 Parliament Street and things were looking up until the Second World War began, when once again the sons and staff left to join the Forces or take up war work. The only son left was Bernard who together with those who for various reasons could not join up, carried the company through the dark years of 1939-1945. No new furniture was made during the war years, apart from some Utility furniture which was extremely limited, so it was fortuitous that the warehouse was filled with furniture from before the outbreak of war. The second youngest son, Claude, took on the management of the removals side and kept on after the war on his own but later returned to the main furniture business in 1953.

Further development of premises on Parliament Street/Milton Street was undertaken after the war, but sadly to no avail as they were informed by the City Engineer’s department that they were going to compulsorily acquire the site and demolish the building and build a roundabout at the bottom of Milton Street. To find another suitable building proved to be no easy task because of cost and the necessity to have premises with enough space to house all the furniture. The building on the south side of Parliament Street known as Burton Buildings was purchased but converting what was essentially three separate shops and office space, again caused problems but eventually the premises were made ready for the business only to find that the Corporation had decided not to make the roundabout, so Hopewells remained on both sides of Parliament Street. By the late 1950s premises had been taken on Dame Agnes Street as a warehouse but with large swathes of this area earmarked for demolition the same problems were going to keep arising and it was decided to look for somewhere large enough to house all the stock and showrooms and central to the city centre. In 1966 an extensive site on Huntingdon Street and Great Freeman Street was taken on a 99 year lease from Nottingham City Corporation. Huntingdon Street was already earmarked for development, so the new store would be in the hub of the city. It took a further seven years before the store was up and running and another three years for the warehousing completed in 1976.

The company was very progressive and began introducing Danish and Scandinavian furniture to the customers a long time before other stores caught on. The store today still retails in a wide variety of furniture to suit most people. Departments have been added to the store’s base including, carpeting, fitted furniture and designing for industry as well as the supply of furniture and fittings. Hopewells has reflected social change with the growth of motor transport and mechanised production, the introduction of hire purchase and with communications came the ability to source furniture from around the world. The displays within the store have won awards. Two new shops were opened, one in Derby the other in Leicester, which was later destroyed by fire. In 2004, the Derby store had to close under threat of compulsory purchase for the expansion of the Westfield Centre and was reluctantly sold and regrettably there was no available opportunity to replace within the centre.

The company has remained loyal to its traditional standards in providing quality, value and individuality and giving satisfaction. Hopewells has a very loyal customer base and most of the 80 staff have been with the company for some considerable time. The store has a vast showroom space and on-site parking, both of which are beneficial to sales. In April 1985, in the store’s centenary year, Bernard, who had steered Hopewells for 50 years died. He had been the visionary in transforming it from a small time furniture store to a company with a reputation which was known far and wide. The Hopewell family, second and third generation, still play a major role in running the business; John the son of Eric is Chairman, Adam, Eric’s grandson and his wife are Directors of the company. In 2010 they celebrated their 125th anniversary and the store is still a significant company in Nottingham.

Griffin and Spalding (Debenhams)

Griffin and Spalding on Long Row, c.1905.

The outstanding building on the corner of Market Street and Long Row has long been associated with the firm of Griffin and Spalding. Its name changed in 1973 to Debenhams but had in fact been part of that group since 1944.

Like many of the other earlier twentieth century stores in Nottingham, such as Jessop and Sons, Pearson Brothers, Tobys and Burtons, the beginnings of this store can be traced back to the mid-nineteenth century. In 1846 Robert and Edward Dickinson opened a store on the corner of Market Street and Long Row selling clothing. When these brothers retired a Mr Fazackerly carried on the shop until he died in 1878.

It was then that the store was purchased by W Griffin and J T Spalding. Mr Spalding had been apprenticed to Marshall and Snelgrove in London, so had a sound background in running a department store. They were excellent traders and ten years after their purchase of the store in 1888 they had saved enough money to begin a major rebuilding scheme and were able to acquire the buildings on either side of the original store. Further improvements were made and in 1924 sections of the store on Market Street and Long Row were rebuilt with a facing of Portland Stone, indicating the magnificence of the store. J T Spalding had been a Justice of the Peace in Nottingham and died at the age of 82 years, but his two sons, William A and Major Harold Spalding, took over from their father. W Griffin died some years later, in 1932 at the age of 90 years and was followed by his son, Perry Griffin. The store was run by these men until 1944 when it was decided to accept an offer from Debenhams who would have a controlling interest.

The store had always carried a varied and large stock of goods, for example, clothing (including furs), furnishings and household wares. They were able to charge competitive rates and they offered 10/- (50p) to the first person who could report the same item being sold more cheaply by competitors. The experienced staff were known for their courtesy to customers and were well looked after by the company and in 1935 female staff were given accommodation on St Ann’s Hill.

One department which is probably not associated with the store was that of Cinema furnishings. During the 1930s this was a flourishing department and was run from the factory on Rutland Street, Nottingham. Two cinemas which had their seating and carpeting replaced in 1934 were the Savoy cinema on Derby Road and the Curzon Cinema (no longer a cinema) on Mansfield Road, Sherwood.

Another department which was well known to the people of Nottingham was the Mikado Café, a convivial meeting place for shoppers and visitors to the city, was situated to the right of the main store. A contemporary article noted that the Mikado Café was centred in “a fashionable store in town noted for high fashion and furs and has something of a reputation of the seafront at Brighton as a place where people liked to be seen in the latest fashions.”

In 1951 a modernisation to develop and extend the women’s wear department was undertaken. One of the problems facing the store was that over time the store had expanded taking in seven different buildings which because of its intricate interiors meant it was built on 37 different floors! In 1978 there were 30 shops within the one main store. In 1985 Debenhams was taken over by the Burton Group but they continued to use the Debenhams name. In November 1988 a multi-thousand pound overall took place which made every floor accessible by escalator, followed by a similar makeover in 1998.

The store has now been in existence for 168 years under one name or another, selling similar goods to those at its inception. It is a landmark in the city and is one of the few long standing stores associated with Nottingham.

Jessops (John Lewis)

Once again this department store has its origins in the early 19th century. The very first store was founded by John Townsend when on 22 September 1804 he gave notification of his intent to open a shop. Originally it was on Long Row, next to the Black Boy Inn (now Primark). The shop sold haberdashery and millinery. In 1832 he became partners with a William Daft, whose parents had owned the Robin Hood and Little John public house at Arnold. Sometime later after Townsend had retired, Daft was then joined Zebedee Jessop in 1860 and the partnership carried on until Daft’s death in 1860 at the age of 63 years. Jessop carried on alone until his eldest son, William, joined him in 1880 when the firm became Jessop and Son.

The Jessops shop on King Street (image courtesy of Local Studies, Nottingham Central Library).

In 1897 the lease on the Long Row store expired and the store was relocated to 16 King Street, where it remained for 75 years. Zebedee had been a personal friend of Mr Marshall of Marshall and Snelgrove, London. He modelled his store on the London one by carrying the same class of merchandise. The father-son partnership continued until Zebedee’s death at the age of 83 years in 1907. William controlled the shop until 1919 but not without some problems. He was an energetic businessman, thrifty and was known for his struggle against compulsory early closing. The 1912 Shop’s Act made it compulsory to close for half a day. Despite a memorial from his assistants stating that they were working under ‘most favourable conditions’, he was prosecuted by the Nottingham Corporation on several occasions but continued to ignore the summonses and the fine was increased to the maximum of £10. After two years of refusing to accept this legislation he put a ‘black-edged’ notice in the window stating that ‘until further notice the store would close every Thursday afternoon.’

The staff appeared to be well looked after by Jessop and in the beginning staff lived above the shop but by the 1900s most of the lady assistants were living in a hostel on Park Road and later in the Hermitage in the Park. The top door on King Street was emblazoned with ‘Winchelsea House’ and gave entrance to the upstairs living quarters on the top floor and workroom employers who were employed making made-to-measure garments for the customers. The store had a reputation for quality and workmanship and William Jessop kept a tight rein on the store only allowing four or five buyers into it as he did most of the buying.

The store was now selling household furniture, lace curtains, hosiery mantles, gown, shawls and ladies outfittings and fashion accessories including furs. Much of the merchandise was purchased from Marshall and Snelgrove in London. There was also a full funeral service including mourning garments. The store at the turn of the nineteenth century was typical of its time serving the wealthy patrons, many of whom were in the lace trade. Over 80% of the trade was done through credit with only between 10% and 20% in cash transactions. There were over 1,000 credit accounts. The paperwork was done by hand by a team of staff who did not have a typewriter until 1920! Delivery of goods were by porters who carried the goods in light wooden cases on their shoulders. For heavier items a hand cart was used. In 1919 the store moved into a new era and installed a lift which had become a necessity when rebuilding the upper floors for showrooms rather than work rooms.

William died on 22 February 1919 a tired and sick man and was superseded by a Board of Directors with two of William’s sisters on it (there were four sisters). In 1922 it became a limited company with some family input. Fortunes fluctuated during the 1920s and eventually the company was bought by the John Lewis Partnership in 1933. Jessop and Son was the first provincial branch of John Lewis and was developed as a partnership store, increasing the range of merchandise as well as the floor space. It was the son of John Lewis, John Spedan Lewis who coined the phrase, ‘never knowingly undersold’ and introduced the partnership concept with staff benefits; the harder they worked the more they would reap the rewards, the more money they made in the store the greater their bonus at the end of the year. There were improvements in their wages, holidays and closing times.

The period during the Second World War was difficult but the company survived. A new department of soft furnishings and later carpet and hard furnishings was destroyed in 1940 when an oil bomb hit the store during the night. The company did an excellent trade in second hand furniture during this time and over 76 staff were absent serving in the armed forces during the war.

In 1954 the company celebrated 150 years of trade. After more expansion into Albion Chambers on King Street it was decided in 1972 to move the store to the newly developed Victoria Centre. And on 8 November 1972 the move took place amidst astonishing sights – over 800 mangers and staff stopped the traffic in Parliament Street as they wheeled trolleys full of stock and carried mannequins and tables to the new store – the first store designed in the UK by Harold Barnett a native of New York.

In 2000 plans were put forward for a £20 million extension and in 2002 after major refurbishment the store was rebranded John Lewis Nottingham. Sales in the store soared by 18%. This was in no doubt due to the fact that the company entered into on-line trading in 2001 and the end of one of the greatest shopping traditions in Nottingham, when Jessop’s shop opened for 7-day trading. 2014 sees the 150th anniversary of the John Lewis Company.