Overview

Newark Castle.

Castles appear in England in the mid to late 11th century and become closely bound up in the story of the Norman Conquest. Defining them is difficult, particularly as they change in function throughout the middle ages and embrace monuments of different forms and functions. For instance, castles can be initially split into two groups: the major and the minor, broadly divided between royal and private. Major castles have a national role in politics and defence strategy (e.g. Nottingham). Minor castles have an important social and economic role in their local landscapes but are seldom involved in any conflict more serious than crime.

These functional differences are reflected in design. Major castles are built predominantly in stone and include defensive features such as battlements, portcullis, postern gates, drawbridges, moats and gatehouses. Minor castles tend to remain structures of earth and timber and to reveal little evidence of serious defence. Over time, both categories of castle will see substantial changes to their function and architecture. A major castle may cease to have a strategic role and become instead a palace providing high-status accommodation. Minor castles may be redundant as early as the mid-13th century and slowly become local landmarks and objects of folk memory.

Our working definition is that castles are residences with pretensions: pretensions to defensibility and to status. Castles are built either by the elite, or by those who aspire to join the elite. Today we apply the term to post-medieval buildings as well. Nottingham always has a castle, even though from its 18th century phase onwards we talk of the Ducal palace. A 19th century terraced house can be called ‘Castle Villas’. On the other hand, Wollaton Hall is never Wollaton Castle, despite the fact that its design is very ‘castle’-like with its central tower and surrounding turreted curtain. We cannot assume that all castles conform to any one definition.

Nottinghamshire is an inland county remote from any major borders in the middle ages. It has a low density of castles – a mere one to 70.3 square miles as of D.J.C.King’s 1983 survey. This is perhaps because it is involved in so little conflict but, more likely, because castle building is constrained by the scale of the royal forest of Sherwood. Sherwood at its greatest extent occupied 100,000 acres or 20% of the county. The restrictions this brought with it resulted in fewer major lords residing in Nottinghamshire – another factor to reduce the number of castles built.

There are currently about 20 sites in Nottinghamshire categorised as castles. This includes the major stone castles of Nottingham, owned by the Crown, and Newark, built for the Bishops of Lincoln. The minor castles seem predominantly to be earth and timber castles (occasionally with some evidence of stonework) of likely late 11th and 12th century date. They include Annesley, Aslockton, Bothamsall, Cuckney, East Bridgford, Egmanton, Haughton, Laxton, Lowdham and Worksop. Documentary evidence places Jordan’s Castle at Wellow into the 13th century whilst Greasley Castle conforms to the mid-14th century penchant for quadrangular castles. Halloughton near Southwell and Strelley Hall both have ‘tower houses’ of a style more commonly found in Northumberland and Scotland. Kirkby in Ashfield and Kingshaugh, near Tuxford, both have earthwork remains that are difficult to interpret while a medieval chronicler reports that Southwell Minster was fortified with a ditch and bank during the 1140s civil war between Stephen and Matilda. In fact many of the sites are open to different interpretations – no two authors will come up with the same list of Nottinghamshire ‘castles’ as each will have their own definition of the monument type. It is likely that there are unrecognised castle sites. Certainly there are confusions in the medieval records. Blyth for example is sometimes referred to as a castle whereas it is clear from the records of the Benedictine priory of Blyth that the castle is actually Tickhill, just over the border in South Yorkshire. Annesley possesses both a motte and bailey castle, referred to in 13th century perambulations of Sherwood Forest, and a ‘strong house’, ‘built after such a manner that it was thought it might chance to bring injury to the neighbouring parts’, by Reginald Mark in 1220, brother of the sheriff of Nottingham. One useful tool when researching Nottinghamshire’s castles is the itinerary of King John (1199-1216). John is recorded as having stayed at Aslockton, Lowdham, Gunthorpe, Kingshaugh and Clipstone. The inference to be drawn is that these sites had suitable premises for a royal visit – perhaps a castle?

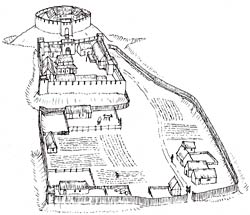

Reconstruction drawing of Laxton Castle, c.1200.

Reconstruction drawing of Laxton Castle, c.1200.There are standard formats that recur again and again in castle design and can be used to assist in the assessment of a monument. The earliest castles were either motte and baileys or ringworks. The motte was a pudding shaped hill, either an entirely artificial construction of alternating layers of turf, earth, sand, gravel, rubble, wood, clay, or a part-natural hillock or promontory that could be scarped to provide the required shape. It was surrounded by a dry ditch or very occasionally a wet moat (for example it is the lack of a motte ditch at Aslockton that casts doubt upon its interpretation as a castle). The bailey was a ditched and embanked enclosure. One or more of these articulated with the motte, providing ancillary enclosures used for the everyday activities of the castle (food preparation, accommodation, craft work, stabling). The ringwork was essentially a bailey without a motte. However, as a freestanding structure it tended to be stronger, with a broader and higher bank and ditch system, and an interior ground level that was higher than that outside. In general we can assume that a ringwork was either earlier in date than a neighbouring motte and bailey, or perhaps the home of an absentee or less wealthy lord.

Whilst these formats are recognisable and therefore useful, it is crucial to remember that these minor castles have suffered erosion, damage, landscaping, and the removal of, or addition of, features since their original construction. The version that we see today is a modern rather than medieval one. With the exception of Nottingham and Newark, the county’s castles also suffer from a lack of documentary evidence and modern fieldwork. This makes it extremely difficult to assess their significance within the medieval period. There were very limited excavations at Lowdham and Greasley in the 1930s, and church related works at Cuckney in the 1950s. In all cases crucial evidence has been lost or misinterpreted.

In 2004/5 geophysical surveys were carried out at Worksop, Annesley, and Wellow (Jordan’s Castle) castles by Pre-Construct Geophysics (Lincoln). The motte at Annesley is heavily tree-covered and impossible to survey but it can be seen to have a steep slope to its south and to be formidable without the aid of any apparent ditch. Its two baileys are of very different characters, delineated by a surviving bank running between them. Gradiometry revealed four curvilinear ditches hitherto undetected, all without ditches. There was also evidence of ridge and furrow. Whilst geophysics are highly unlikely to pick up the traces of wooden buildings, there is new evidence for enclosures that may represent buildings. The general picture emerging is of a site far more complex than hitherto realised. Unfortunately post-medieval landscaping at Worksop meant that the geophysics results here were inconclusive. Results are still awaited from the work at Wellow.

A ground survey was carried out in 2003 at Egmanton castle by the East Midlands Earthwork project (EMEP). This focused upon understanding the development of the monument, recording its surviving remains and matching these to the 19th century evidence from Ordnance survey and other maps. Ground survey and geophysical surveys are currently ongoing at both Laxton and Greasley castles.

Medieval castles served a variety of functions to their communities. In essence they were built by lords to mark their control of manors and towns and to act as estate centres. Each castle was a caput, a chief place or headquarters, from which a wide range of estates, small and large, were managed. They provided homes, guest accommodation, country retreats, centres of law and justice, places of storage and collection, and visible signs of lordship. Their religious role was crucial. Castle lords employed chaplains and other clerics, with the greater castles having up to a dozen clergy by the end of the middle ages. Castles had chapels; private oratories for the lord and his family, larger spaces for the household positioned over the gatehouse or free-standing in the bailey. Unfortunately, the evidence for these in minor castles is often lost although the close juxtaposition of castle and church may be noticeable (e.g. Egmanton), implying that the parish priest doubled up as the castle chaplain.

Spatial analysis of stone castles reveals the presence of one-way systems, processional ways, the framing of lordly thrones by dais and windows, the elaborate decoration of the most visible external elevations, provision of waiting rooms in advance of audience chambers and other features that allow us to work out circulation and access patterns, and the social segregation of space. Earthwork castles can also benefit from such studies. We can look for ‘hierarchies’ within earthworks, comparing enclosure size, regularity, definition and access to work out major and minor entrances, elite and non-elite spaces, and any relationship with associated settlements (e.g. Laxton).

With the exception of Aslockton, Nottinghamshire’s castles are built north of the River Trent, a fact that has caused much discussion amongst archaeologists seeking to position Nottinghamshire as ‘border’ country in the 11th and 12th centuries. Yet their locations can be seen to have more to do with settlement and communication than with defence. Several are located within easy reach of the Great North Road (Laxton, Cuckney, Bothamsall, Wellow, Kingshaugh and Egmanton) or of the navigable Trent (Newark, Nottingham, Lowdham, East Bridgford).The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does record King William and his men constructing castles ‘everywhere in that region’ after the building of Nottingham and York in 1068. However, neither archaeological nor documentary evidence can tie Nottinghamshire’s minor sites to this statement. The most obvious facet of the location of the minor castles is that they are accessible to settlements and therefore to markets, to trade, and to resources.

The castle lords of Nottinghamshire, with the exception of the King at Nottingham and Bishop of Lincoln at Newark, were minor characters. Ilbert de Lacy, the 12th century lord of Pontefract, was an absentee lord of land in Aslockton and Lowdham, but we cannot be certain that he built the castles here. The de Caux and Everingham lords of Laxton were regionally important forest officers but, like their neighbours the Deyvilles of Egmanton, they had relocated north to Yorkshire by the end of the 14th century. The de Lovetots of Worksop were the 12th century lords of Hallamshire with a caput at Sheffield. The general pattern is that where we have a documented lord, he is often absent further north and appears to be using his Nottinghamshire estates as a form of supplementary income. This does not mean that Nottinghamshire’s castles are unimportant, rather that their importance lies in their ‘normal’ roles in a largely peaceful inland county.

Whilst there are several general surveys of British castles, there has been little publication to date specifically on Nottinghamshire sites. Research has to start from one of two directions: the general castle literature or the general Nottinghamshire literature. Useful overviews and suggestions for research angles can be found in:

- Robert Liddiard (2005), Teaching Medieval Castles, The Higher Education Academy website at http://hca.ltsn.ac.uk/resources/overnight_expert/overnight.php?who=med_cast, and

- Carenza Lewis ( 2001), An Archaeological Resource Assessment and Research Agenda for the Medieval Period in the East Midlands 850-1500, www.le.ac.uk/archaeology/pdf_files/emidmed.pdf.

In 1983 David Cathcart King published a monumental 2-volume gazetteer of known castle sites in England and Wales. This is now out of date but it represents a valuable starting point and usefully provides further references for individual sites. If starting from Nottinghamshire, Michael Brook’s Nottinghamshire Bibliography (2002), published as volume 42 of the Thoroton Society Record Series is indispensable. This can be supplemented by consulting the Sites and Monuments Record held by Nottinghamshire County Council at Trent Bridge House in West Bridgford to see if there is a castle or earthwork listed for your area.

Few of these castles are in use today. Nottingham is a museum, Newark a visitor attraction, Worksop a public park. Kingshaugh, Wellow and Egmanton nestle around later houses while Greasley is a farm (with the medieval hall now part of a cattle shed and milking parlour). Laxton is owned by the Crown Estate but is accessible to visitors as long as you take note of the cattle (and bull) grazing in the baileys. Most of the county’s castles are privately owned and not publicly accessible (although footpaths may pass close by). The Nottinghamshire Heritage Gateway advises all researchers to check access and seek permission as appropriate before entering sites.

Nottinghamshire’s castles are currently (2004-2007) enjoying a flurry of interest largely due to the work of the Archaeology team within Nottinghamshire County Council, and the East Midlands Earthwork Project based at the School of Education, University of Nottingham. Members of both groups have been crucial in advancing knowledge of many sites and thanks for their comments on this article go to James Wright, Barry Crisp, Brian Hodgkinson, Sue Hadcock and Richard Skinner.